Interview with Anna Buckner

Interview with Anna Buckner

March 2020 Digital Resident

Mineral House Media: Tell us a little bit about yourself and your background in art.

Anna Buckner: I grew up in Greensboro, NC. My parents met in grad school at UNCG - my dad was studying painting and my mom studied dance. Back then, pre-Anna days, my mom would sometimes model for my dad’s life drawing classes so we had all of these nude paintings of my mom around the house growing up. In reality, it was probably 2 or 3 paintings, but it felt like our house was covered in them. I have this distinct memory of my sister and I frantically running around the house taking them down and hiding them in a closet before one of her birthday parties.

I feel lucky to have been exposed to the arts from such a young age. My mom would take me to these wild dances put on by the university - I remember seeing a fully nude dance at around age 7. My dad set up still lifes for me to paint early on - he had so many books about art, and we’d look through them together, and then set up fruit to paint side by side. They were really my first teachers - they made art central to everything we did.

MHM: What originally brought you to your interest in quilt patterns?

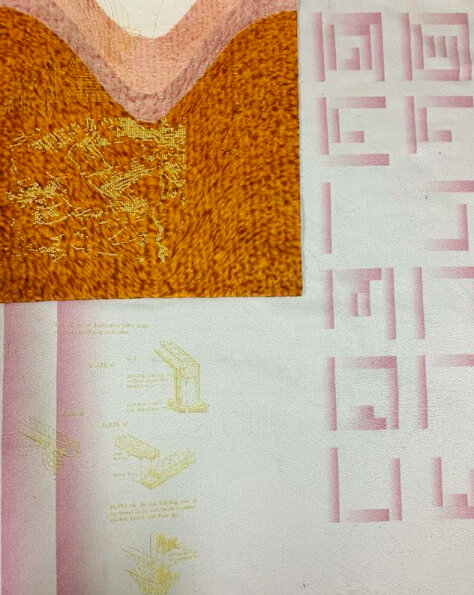

AB: My great-grandmother quilted, and so I grew up with some of her old quilts, but it wasn’t really until grad school that I started thinking about the patterns. I was at Indiana University, getting my MFA in painting, thinking deeply about the history and structure of painting. At this point, I became interested in the support and substrate of a painting - the stretchers and the linen or canvas. I wanted to make work that called attention to all aspects of a painting - the fabric, the support, the image. Quilting felt like a natural way to do this. I took a course on piecework from Aaron McIntosh at Penland. I was trying a lot of patterns, but after a little reflection years later it became clear that I was fixated on one in particular - that one was the log cabin quilt pattern.

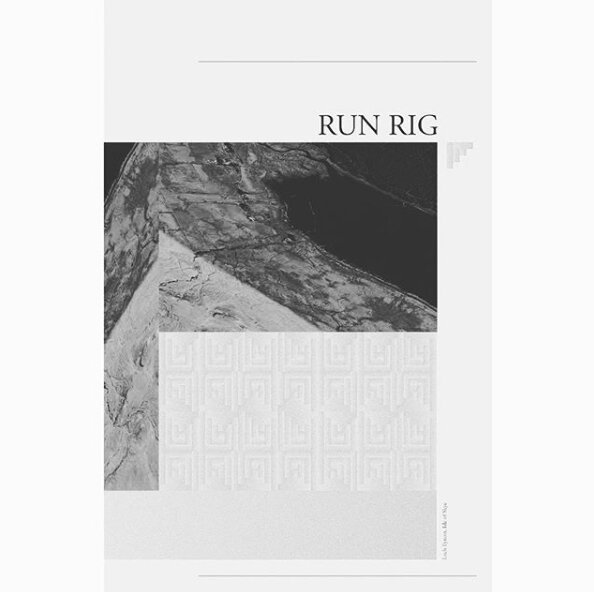

MHM: Some of your works are inspired by historical farming patterns. Can you tell us more about the medieval Scottish farming practice, “run rig farming”? How does this influence your quilt making?

AB: After using this pattern over and over again in my work, I wanted to learn more about its history and possible origins. I read about this one in Janet Rae’s book, Making Connections. It’s a theory, but when you look at some versions of log cabin quilts and images of this farming practice the similarities are striking. I’m not sure yet how this influences my own making, but I am curious about all possible origins. We have this idea of what the log cabin pattern is - that it’s quintessentially American, representative of colonial expanse through the building of cabins. But introducing these other origins start to open up the conversation. The naming “log cabin” indicates a false singular narrative. I use it for the sake of clarity, but I’d like to come up with something that celebrates the pattern’s multiple narratives.

Anna Buckner, Something About That Tree, 2017. Acrylic and gouache on pieced fabric on stretcher. 48” x 36” (Image courtesy of the artist)

MHM: How do you go about collecting fabric and materials for your works? What aesthetic or sentimental value do you look for?

AB: Initially I was looking for fabric that embraced a sense of flexibility - colors that are difficult to name that could change easily depending on adjacent colors, textures that shift in different lights, stretchy fabrics that morph when stretched on a frame. I like fabrics that are worn and have a history rather than fabrics straight off the shelf. A lot of the time I use old clothing - sentimental pieces that are too old to wear or donate but too precious to throw away.

MHM: Your fabric paintings have a warbling fluidity that contrasts with the structural intensity of their patterns. Can you give us some insight into the process for creating this movement in your pieces, and what this dualistic angularity/softness means for you conceptually?

AB: I make the piecework first before stretching. A lot of the fabrics I select are stretchy - I like fabrics that shift (grow) when I put them on stretchers. This process is an embrace of the unknown - something that doesn’t really come easily for me. But with these paintings I learned to welcome it - I never know how these are going to turn out and that not knowing has now become a central part of the process. I think ultimately I am trying to strike a balance between control (the angularity of the pattern, perhaps) and the unknown (fluidity, change, softness). I guess I figured if I could strike this balance in a painting then maybe I could start applying these ideas to the rest of my life.

MHM: Do you sew most of your work by hand? How do you feel the manual or repetitive tasks involved in your paintings affect you personally?

AB: I do all of the piecework on my grandmother’s old Singer sewing machine from the 1930s - it works more consistently than any other sewing machine I’ve used. She died in 2012, but it still smells like her. When I do quilt (binding the quilt top, batting and backing together), I like to sew by hand. This is slow and careful work. It keeps me present.

Anna Buckner, Flesh and Ochre, 2015. Pieced fabric on stretcher. 36” x 24” (Image courtesy of the artist)

MHM: When you mention the “poetic possibilities of pattern,” it brings to mind the encryption practices in some historic quilting methods, like those used in connection with the Underground Railroad. Do you view your works as containing direct signification or encrypted information?

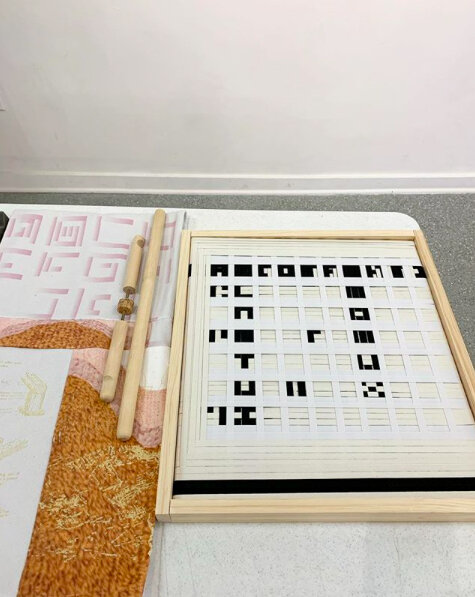

AB: There is certainly a sense of mystery with the pattern that feels like encryption. I suppose that’s why I’m drawn to it, and why I am able to find so many possible origin myths - so many cultures who have used this pattern. In my work I’m not thinking of anything as specific as that, but rather what the pattern can be used for. How else can we apply the system? I’ve recently used the pattern for a typographic system, and I’m starting to collaborate with my mom to see how a dancer might play with the pattern. I like to get into the habit of treating everything I do as a study - where I’m asking questions rather than making statements.

MHM: You draw from a wide range of international and historical influences. Do any personal travel experiences influence your connection to these themes?

AB: I’ve never been to Egypt and I’ve only seen remnants of the run-rig practices via Google Earth. It certainly makes me want to go to these places. My partner is Swedish, and I’ve traveled with him there a couple of times to visit his dad and to see the country (it didn’t take me long to embrace sauna culture.) Travel is tricky because I want to do so much more of it, but I also understand the environmental implications of flying.

Anna Buckner, Deep End, 2016. Acrylic, flashe and oil on fabric scraps on stretcher. 60" x 40" (Image courtesy of the artist)

MHM: The three main influences for your current works (Egyptian cat mummies, Scandinavian bath houses, and Scottish farming practices) each seem deeply tied to land or environment. What role does your interaction with the natural world play in your daily life and thought process?

AB: I’m glad you said that. I think that ultimately the pattern is a reflection of the environment - of cyclical growth in nature. I find a sense of spirituality in the pattern, and I think its ties to the land speak to its ubiquity.

MHM: The connection to sowing land and sewing fabric is very interesting. In this reference to farming, do you see any of your works as abstract landscapes?

AB: That’s an interesting connection. I think a lot of them are landscapes. I finally am living in a place where I feel a little more settled - we have a garden and are able to grow vegetables. I’ve always had this really romantic idea about farming and sowing land. In practice, it’s hard work and slow. I honestly felt the same way about sewing quilts when I started. I think both processes slow us down and focus on the present and I think I could use a little more of that.

MHM: Are you drawn to making works on a smaller scale, or do you see your current works developing into larger pieces?

AB: When I started this process in 2015 I played with scale quite a bit - I had a huge studio while at IU. The honest, but maybe boring answer is that the scale of my work is generally directly related to the size of my studio. Right now my studio is small, so the work I’m making is small.

MHM: By making towels, you embed a sense of everyday usefulness into your pieces, highlighting the roots of your research into utilitarian objects and practices. Do you feel that you are challenging fine art norms which often reject utility?

AB: I hope that a rejection of utility is becoming less of a norm.

MHM: How has social distancing due to the Coronavirus pandemic affected or altered your work/process? Has it made you think of your work in any new ways, or introduced a different perspective?

AB: When this started I had all these ambitious goals for my studio practice. Instead, my focus has been more on transitioning my teaching online. When I’m not doing that I’m baking bread, growing herbs and vegetables, and quilting. Transitions are difficult (I always forget this), and I haven’t had inspiration to push my ideas further. This residency (and this time in general) has been more about reconnecting to the home. It’s not what I expected.

Anna Buckner, Indiana Mountain, 2017. acrylic and gouache on pieced fabric on stretcher. 18” x 16” (Image courtesy of the artist)

MHM: During this time, it is so important to think of community and ways we can connect with each other and support one another. In one of your Instagram posts you said, ”I’m thinking a lot about relationships, connection, and how we can take better care of each other and of the planet.” Can you elaborate on these thoughts and how they are influencing your daily practices?

AB: I see log cabin patterns as being inherently tied to nature - in all origin possibilities of the pattern there is a connection to the earth. The pattern is a good reminder of our own relationships - both with each other and the environment. Unfortunately, so is this virus. Many of us are staying home to protect each other, and in doing so we are shedding light on the way our actions affect the environment - less air travel has created a dip in greenhouse gas emissions. Of course, this will increase once the stay at home orders are lifted, but I hope folks are paying attention to these changes and that the movement to fly less takes off.

MHM: Log cabins are representative of the home, and domesticity. How does researching historical structures of the home affect the way you think of modern homes and the modern community?

AB: There is so much care that goes into building a log cabin or making a quilt. They are slow processes - and I think in that slowness makers have the time to form relationships and a sense of respect with materials and with place. I worry about a lot of modern homes - prefab buildings that are essentially designed to last a couple of decades. I think we’ve lost a sense of reverence to material. Maybe with this time people will form a stronger relationship with home and domesticity and that sense of reverence will grow.

Anna Buckner is an interdisciplinary maker and educator, interested in exploring the limits of existing structures and systems of logic within painting, language, textile patterning, new media, and emerging modes of teaching and learning. Her work has been exhibited nationally, including solo and group exhibitions at Bad Water in Knoxville, TN, Markel Fine Arts in New York City, The Museum of Human Achievement in Austin, TX, Grunwald Gallery in Bloomington, IN, The Painting Center in New York City, Marian University in Indianapolis, IN, among others.