Interview with Jennifer Crescuillo

Interview with Jennifer Crescuillo

April 2020 Digital Resident

“I am interested in what makes an object appear primitive/advanced, ancient/modern, old/new. My work is about exploring the visual cues that can signal age, whether that be through evidence of weathering or use, or through nostalgia. Our contemporary society’s willingness to discard ‘old’ items for ‘new’ items even if there is no functional need, are themes that run strong in much of my work. My practice involves drawing and photographing objects and textures coupled with techniques such as mold making, casting and hand finishing to emphasize a connection to natural processes such as fossilization and weathering. I use retro objects such as cassettes and radios and video games from the 1980’ and 90’s because those are the type of objects I remember growing up with during that time. Those were the objects that were ‘brand new’ and ‘cutting edge’, but today as an adult I look back at those objects and now they are ‘old’ and ‘useless’ compared to things like Ipads and smartphones. The combination of these objects with natural crystal forms and fossilized textures connects them to the geologic timeline of ‘obsolete’ items from the entire history of human kind. I try to explore this idea and transformation in a variety of different iterations and facets to understand it more deeply.”

-Jennifer Crescuillo

Mineral House Media: How did you first get involved with glass, and how has your practice changed over the years?

Jennifer Crescuillo: I first found glass while I was an undergrad at Bowling Green State University in Ohio. I was originally in the sculpture department and glass was right next door across the courtyard and it was warm, and had fun music blaring, and loud funny people and I got totally sucked in. All us Glassies are the same, like moths to the flame, literally.

MHM: In your series Future Fossils, you work with concepts of "primitive, ancient, and modern technology”. Can you expand on your definition of technology, and how you conceptualize technological fossils?

JC: I think of technology broadly as any human invention. Over the course of human history technology builds upon the inventions that have come before, and compounds on itself until we are here in the current day. Each new invention is revolutionary and novel in its time, but when we look back on items from the past they seem antiquated. The same exact item that was revolutionary in its debut, having undergone no physical change, becomes irrelevant. For instance, the Ipod. It completely changed the way we think of music portability and curated playlists, it made a bunch of other devices superfluous (Walkman, Discman, remember those AM/FM tuner headphones that were so huge!?), but now the first (or any) stand-alone music player seems silly compared to using our phones and streaming services. The Ipod is just one device in a long lineage of music listening tools that we have developed, and the technologies of music recording and listening is just one vein of human invention. I like to use the iconography of radios, music players, video games, etc because these are technologies that most people have some intimate exposure to and can see the technological advancements clearly throughout their lifetime. The ideas of ‘primitive, ancient and modern’ that I am interested in are the visual language we think of as being associated with fossils and artifacts of extreme age. Crystallization, cracking, discoloration, etc. Most of us alive today have no experience with extremely old artifacts in our everyday lives so I choose to combine the visual texture of ancient fossils and tools with more contemporary iconography to tie those ideas together.

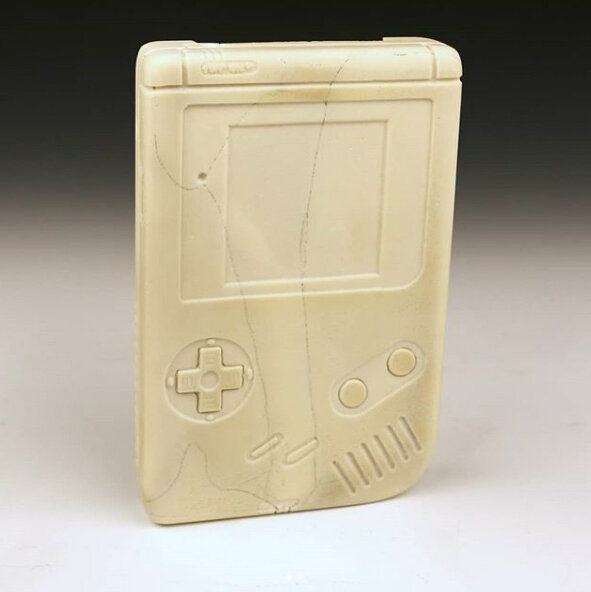

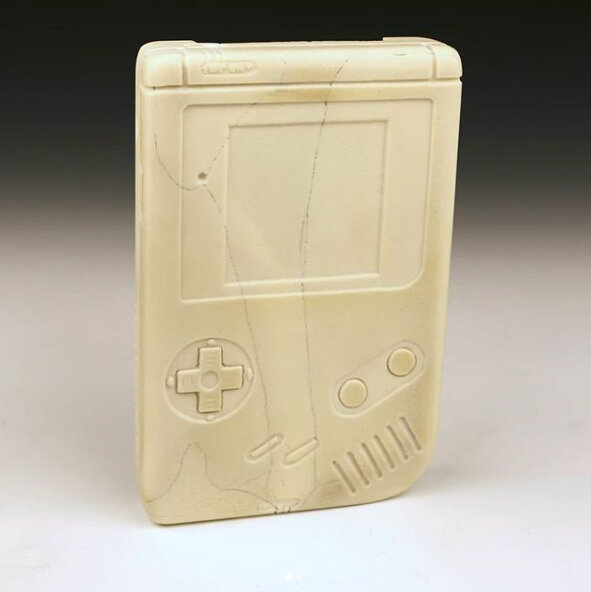

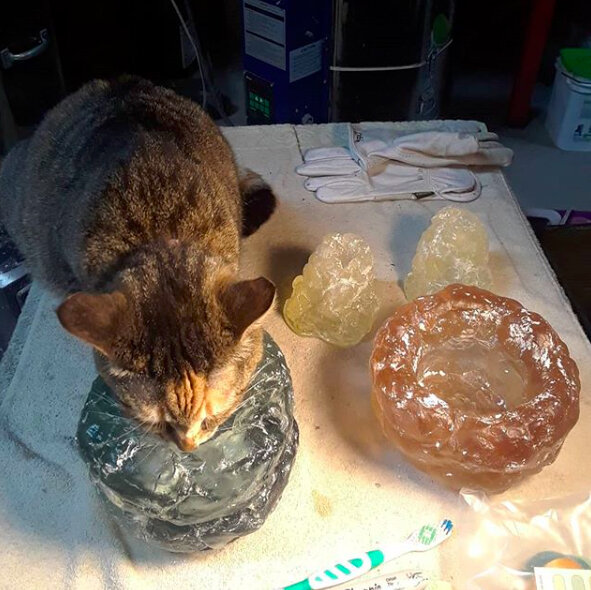

Personal Meditation Device/Game Boy, fused and carved glass. Jennifer Crescuillo.

MHM: You challenge our “willingness to discard obsolete items” by replicating those items (like Personal Meditation Device/Game Boy) with great care. Can you talk about your process for creating the carved glass pieces?

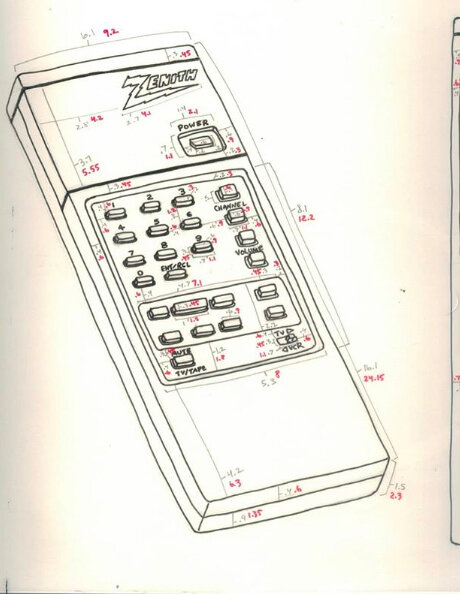

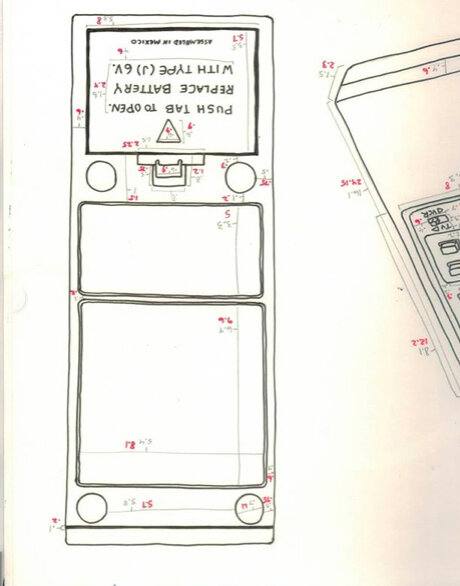

JC: First I find the item I want to recreate on ebay or at the thrift store. It is too hard to just look at pictures, it makes it so much easier to just have the item. Then I do some orthographic drawings of the ‘thing’ to record the details I want to include, the measurements and proportion. Then I scale up all the measurements by 1.5. I use this drawing as my blueprint for the final sculpture. Then I create a glass block of the appropriate size by melting together sheets or shards of glass in a kiln at around 1600 degrees F. Once the glass is cooled I can carve it like a block of stone. What is nice about using glass instead of stone is that I can melt whatever size and shape I would like initially, and I can control the color and interior texture of the glass. I have worked with stone before as well, I just prefer the variation possible with glass. Next I refine the overall shape of the glass and cover it with a rubbery resist for sandblasting. Then I transfer my drawing to the resist and carve the detail with the sandblaster until I have removed all of the resist. Then I sometimes buff the surface or apply paint or oils, depending on the individual piece.

I like the crystal and mineral textures that the glass can develop in the kiln that is enhanced during the sandblasting process. Real stone and crystals melt at a much much too high temperature and are pretty unstable, the glass does a perfect job of mimicking them in a controllable way.

MHM: Why do you feel these carved glass pieces are best presented as larger than life?

JC: It gives them a nicer presence in a gallery space, first of all. Also, ‘techy’ objects seem to always be getting smaller and slimmer, so to increase the clunkiness and bulkiness of these objects makes them seem even older. We also remember many things from our childhood as being bigger than they actually were, I am trying to play on that feeling.

Turd Bowls, Jennifer Crescuillo.

MHM: The new pieces in your Everything is Shit series are a hilarious take on the way fossilization increases the value of mundane, even abject objects. Can you expand on this work and its place in your ideation of archaeological practices?

JC: Yes, coprolites, fossilized dino poo. I hadn’t yet made that connection! I was first inspired to make those pieces by the current trend of ‘poopy ceramics’ that is everywhere I look. The crustier and crappier and lumpier the better it seems. I thought it would transfer well to glass and I have zero skill as a ceramicist so I embraced my crappiness at it by making ‘turd shapes’. I also love Wim Delvoye’s piece Cloaca, that is a literal turd machine. And his turd tiled bathroom and all his work. He has some amazing stained glass windows that are not poo related. Also, everything is shit right now anyway, so why not glass? I like being a little shit, so it fits my personality too. Everyone likes a poop joke, bathroom humor, it has it all.

MHM: Some of your work focuses on the power of glass to captivate and evoke a sense of mystery. Do you feel that we owe a degree of our spiritual natures to the effects of glass and its interaction with light?

JC: Yes definitely. Glass is like a man made, man manipulated gemstone. It can be made into any color, any shape, hot formed, cold carved, transparent, opaque, rough, smooth. I don’t know a lot of materials that can transform in so many ways. Glass has been used for centuries in holy spaces as a way to show the holy light of God’s presence in cathedral windows for instance, or as mosaic tiles. But even then glass was imitating precious stones and gems that were rare, expensive, regional, and hard to work. Glass was the technology that made those ideas easier to illustrate to a wider audience. Glass was also made to mimic rock crystal for wine goblets and drinking vessels that were originally carved from large solid chunks of natural quartz. Making transparent ‘glasses’ originally so expensive only the wealthiest royal families owned them. Blown glass vessels, though still a luxury item, were available to a much wider slice of the population. The Corning Museum of Glass has the most comprehensive library about everything glass if anyone is interested. And a killer youtube channel with glass making videos.

Glass has always had a mystery around it because of these associations, as well as the fact that glass making factories and studios are not as much in the public eye as ceramics studios or blacksmiths. Except for the Netflix series Blown Away, if you haven’t seen it!!

MHM: Your work deeply investigates “what makes an object appear primitive/advanced, ancient/modern, old/new.” This brings to mind the many science fiction movies that work to fuse signifiers of the ancient and modern in their set designs. What influences do you study to build your understanding of old/new visual cues, apart from the objects themselves?

JC: I use the visual language of fossilization and weathering from wind, water, sand. Things like crackling, inclusions, layers, think the body of the Sphinx. It is severely weathered, but we can still identify the form. The glass makes a certain amount of these textures naturally which is one reason I like using glass v stone.

MHM: In working to convey both ancient and modern sensations, what is your relationship with color? How do you decide on the coloration of your objects?

JC: I love bright colors and the whole spectrum. But one downside of glass, is that it is difficult to create your own color from scratch. It is somewhat similar to creating your own ceramic glaze, but more dependent on expensive equipment, so I typically find or buy colored glass that I like. I scavenge used glass that has the color i’m after, or glass that I know makes an interesting texture after being fired. A lot of the glass I use is recycled architectural glass from the 30’s, so it naturally has a dated palette. I like to throw in some pops of red, purple, orange, opal for fun and to set off the neutral tones. I enjoy a lot of contrast and complementary color relationships. I am a disciple of the Joself Albers school of color theory and I think about his principles often.

MHM: Who are some of your favorite artists?

JC: Wim Delvoye that I mentioned earlier. Michelangelo, Rodin, Rene Magritte, Josef and Annie Albers, Ettore Sottsass, Ercole Barovier, Napoleone Martinuzzi. Sally Mann, and Etienne-Jules Marey. I’m also very much loving Kristen Liu Wong’s work right now.

MHM: Can you explain the narrative importance of hand finishing and other manual techniques in connecting the lineage of ancient and modern making?

JC: Many of my pieces require hand polishing or buffing of the surface to achieve the final texture. Quite frequently I have to do this by hand with loose grit particulate in the same way stone, metal, glass, rock crystal has been worked for thousands of years before machines were invented for this purpose. A lot of glass techniques remain the same from their initial invention thousands of years ago. Those ancient techniques are still used by me, and many other glass artists to make so many different things. I think that connection to past technique is cool and also relevant to some of my ideas.

MHM: What is the most challenging part of your process?

JC: Honestly, marketing the work after it’s made to galleries for sale or exhibition. I have no shortage of ideas, I have tools and the ability to make what I want to, but I’m not a good salesman. I don’t like doing that part of it either. Also, finding time to be in the studio between work and kids is always a struggle.

MHM: Do you have a preference for hot or cold working your materials? If so, are there elements of that process that inform your relationship with the work?

JC: I do more cold working and carving generally. I have those tools in my studio, it’s a little more economical to do (not much) and it’s what I’ve spent more time perfecting. I like working subtractively, I like the slower pace. I do love blowing glass as well, but studio access is expensive and not close enough to be a regular occurance right now.

MHM: Do you find that there are any particular challenges in being a contemporary glass artist? How do you work to overcome them?

JC: Yes, glass is seen as a decorative medium and has a lot of stereotypes around it when viewed by those in the wider ‘art world’. Dale Chihuly is pretty much the core of it. Chihuly has made some amazing work and is a pioneer and his work transcends glass and becomes sculpture, but few other artists have made that kind of impact, so people imaging glass can only look like his work. I think glass is becoming more prevalent in the last 5 years or so. Also, looking at the trends in what ceramics is doing sculpturally and in contemporary design, I think glass will follow and become recognized more in the near future for its versatility as a medium. That being said I identify myself as a glass artist in certain circles and a sculptor in others to avoid negative stereotypes.

MHM: Your practice demands a high level of material skill, tools, and equipment. What advice would you offer a beginning glass artist, who is still working to build up a studio and practice for themselves?

JC: My advice is that accumulation takes time. All the tools are expensive, they never get cheaper, only more expensive so buy tools when you can and keep them for as long as you can. I have never regretted buying a tool and some have sat in my parent’s barn for a long time until I had a barn of my own. Don’t compare yourself to people who have been working in glass for many years if you are just beginning. Try to be their friend and learn from them. Always keep moving forward even if it’s just a little at a time. Glass people who have been in it for a while are stubborn, persistent, probably should have quit a few times before but didn’t. Define what success means for you, everyone’s path in glass is very different and the only thing that is consistent is not quitting. Also, travel as much as you can and learn from as many different people as you can and don’t work for a-holes. Money is temporary, knowledge and experience can never be taken from you.

Jennifer Crescuillo is an internationally exhibited artist currently living and working in Silver Point, Tennessee with her family. She received her Master’s of Fine Art in glass at Southern Illinois University Carbondale. She has taught and worked at various glass studios, such as The Studio of the Corning Museum of Glass, Urban Glass, and Pilchuck Glass School. Her work has been included in New Glass Review 34, 36, and 38, and she has been a Wheaton Arts Fellow in 2014 and 2017 and an Emerging Artist in Residence at Pilchuck Glass School in 2016 Together with her partner, Andrew Najarian, Jennifer operates High Polish Studio specializing in custom glass fabrication and cold working services.