Interview with Liz Miller

Interview with

Liz Miller

February 2022 Digital Resident

A conversation with Clay Aldridge, Olivia Tawzer, and Victoria Sauer of Mineral House Media

“My recent wall-based fiber works and installation environments explore architecture, boundaries, and borders through the juxtaposition of architectural fragments and fiber-based adornment. Pieces of the built environment, such as components of fences, gutter guards, or metal remnants of domestic interiors (such as stove grates) become armatures for ad-hoc weaving, knotting, and embellishment with rope, cord, and other textile materials. My fascination with rope and knotting started as a byproduct of my large-scale installations, where I utilize rope to achieve tension that gives volume to otherwise flat materials. The varied use of rope and knotting across cultures and history ranges from utilitarian to decorative, and even deadly. I create interdependent knotted topographies that allude to both structure and malleability while also recognizing and elevating aspects of human culture that are neglected, overlooked, or discarded. The repeated act of hand tying integrates an emphatic sense of strength, while the flexibility and nuance of the textile material ensures permutations. The resulting works are only quasi-architectural, providing metaphorical insight laced with humor as related to a variety of structural and systemic behavior.”

-Liz Miller

Mineral House Media: What does a studio day look like for you? Do you have to travel to a studio space? Do you listen to music or podcasts?

Liz Miller: My studio days vary quite a bit, but if I have my choice, I work early. I am a morning person, and most of my good ideas happen before 10 am. We recently remodeled part of the walk-out basement in our house to be my studio. It’s perfect because I’m technically home…but it’s also a place where I don’t allow our standard poodles, where I can be kind of in my own world without all the distractions. I try to leave myself a puzzle to solve at the end of a work day, so that when I show up to studio the next morning, I can dive right in where I left off. I’m a pretty slow and steady worker. It’s a rare day when I make huge gains, but over time, progress happens.

I listen to news in the morning on public radio, for as long as I can take it. Lately I feel like I can’t take it for very long. Sometimes I listen to podcasts. Over the past few years, it felt like there were so many people talking about so many things, all the time—I’ve found myself just craving silence. In the afternoons I like music because it’s the hardest time for me to stay focused. I rarely work in the studio later than 6 pm—if I do, it’s usually focusing on other parts of my practice, such as organizing images, or writing.

MHM: Your work takes a lot of… work. In the relationship between process and product, which do you find more meaningful, if either?

LM: Although I’m ultimately striving for a final product, the process is the way I get there. I find the process frustrating…but ultimately, it’s what leads to breakthroughs in the work. I’ve always been really process-oriented. I often just start experimenting, and that’s how I start to find the logic and meaning in the work. I can sit around for a decade and not think of a single interesting idea. But if you put me in my studio with a bunch of materials, I’ll start to figure it all out. And then I’ll reach back out into the world to connect those findings to the things that are relevant to them.

MHM: Where do you source your materials? Do you re-use material from previous installations?

LM: My approach to materials is broad and varied. I am currently obsessed with the relics of contemporary consumer culture—for example, pieces of cheap closet shelving, shelves from appliances, and other remnants that end up obsolescent and in thrift stores,..or in ditches, and ultimately, in landfills. I search for these items in the hopes that I can elevate them through elaborate weaving and knotting. I find some of them in thrift stores, and some of them in the rural environment where I live, just scattered alongside the rural roads. I also search antique stores for more ornate elements that can serve as a kind of counterpoint to the other reclaimed materials. There’s a kind of “high/low” dialogue that starts to unfold when all this varied stuff is juxtaposed in a single work.

I do also purchase new materials—recent installation projects have utilized snow fencing and gutter guards for example. The rope that is woven through those items is purchased on clearance from an online rope company. They have these clearance assortments of rope called “mystery boxes.” The rope is sold by the pound, so you get a ton of rope…but you have no idea what it will be! I love inserting an element of chance in the work. Although I have to admit I’m always disappointed if I get mostly beige rope. That hasn’t been happening lately—I think they have me figured out!

I try to reuse materials from past installations as much as possible—both as a challenge to myself, and as a way to conserve materials and create less wastefulness in relation to my practice. Sometimes, old installations get taken apart and completely reconfigured into new works in ways where the former iteration is barely recognizable!

MHM: Can you talk a little bit more about the sensation of seeing your wall-based works all together in their first exhibition–Structural Paradigms? It’s very telling that even during a time in the pandemic where not many people were going out to see shows, this experience was still a personal and strong push in a new direction for your work!

LM: Honestly, seeing my Structural Paradigms exhibition go up at David B. Smith Gallery in Denver during spring 2020 was kind of surreal. And not just because of what was happening in the world, but also because I’d worked so hard for so long to figure out how to integrate works other than installations into my practice in a significant way. Seeing them all together (and realizing that no one else would really see them in person due to the pandemic) was kind of emotional--it felt like the start of something new in my career. When you’ve been doing something for a long time, it’s not easy to feel that newness. I have tried to hold onto some of that shiny new feeling in my studio over the past few years, even though there’s plenty of sadness in the world to process.

MHM: Your installations are site-specific, and you seem to be focused on interior sites. This makes sense, as elements of the work are often reminiscent of textiles such as rugs or curtains. However, some of your installations are almost tent-like. Are you interested in potentially creating an installation for an exterior space?

LM: I did a project outdoors on a giant bridge as part of ArtPrize in Grand Rapids, MI nearly a decade ago. The lead-in was filled with logistical challenges, and the actual installation was windy and rainy and expensive. I didn’t enjoy it at all, I didn’t feel good about the outcome on multiple levels, and it kind of scared me away from pursuing more outdoor projects. I’m at a different point in my career now, and I think that I’d definitely consider an outdoor project, but the circumstances would have to be right. I really like to control the situation in the gallery. Working outside, you have to relinquish a lot of control, whereas it’s always 70 degrees and sunny in the gallery. Relinquishing control is not something I’m good at, but something I could probably continue to learn a lot from. Still, as I’ve gotten older, I’ve realized I don’t have to do everything.

MHM: What does starting an installation look like for you? Do you have an idea of the shape, colors, or material of the final piece when you begin?

LM: Starting an installation always begins with materials and experimentation. I have to forget about the space it’s going to be in for a bit, and just let myself mess around with various ideas materially until I find a kind of logic. I sometimes have some idea of what I’m seeking with the choreography of the work through the space, but other times it takes a long time to get to that point. My best works are always the ones where I don’t get too stressed out by the idea that I need to come up with some ginormous thing, and where I just let myself play the way that I would if I was making a small work on paper. It’s not easy to transfer that sense of spontaneity to large, site-specific work because there are so many logistical aspects that have to be considered.

MHM: Besides planning and building installations, are there other important facets of your studio practice such as reading, writing, or drawing?

LM: I love reading, but I often consider the reading I do tangential to my practice as opposed to directly informing it. I have limited time to read, and I don’t like limiting what I’m reading to art books or books that are only about things that seem pertinent to my work. That being said, several of the past few books I’ve read/am reading are things that do have direct relationships to my studio practice. I’m in the middle of The Golden Thread: How Fabric Changed History by Kassia St. Clair. It’s a great read that highlights the unexpected ways that fibers played a role in important historical events.

I used to draw a lot, but haven’t as much recently. I guess if there was something ancillary to my studio practice that I haven’t mentioned, I’d say that maybe it’s simply being a wanderer. I love walking, running, riding my bike, and just browsing in hardware stores, antique stores, etc. Although my studio is kind of my world, the things I bring into my studio are from different worlds, worlds that I can’t gain access to if I don’t do the footwork to engage with spaces and places outside the studio. I know that’s a broad answer, but I think it’s an important one, because even though I’m inclined to sit in my studio day in and day out, it makes for boring work. My work involves an exploration that extends beyond the confines of my studio.

It’s funny you mention writing, because I love language and am an avid crossword puzzler and Scrabble player. Sometimes I make lists of words in relation to my work. I’m not sure what it does for the work, but a simple word can evoke something I’m trying to get at more than a lengthy description in some instances. The words are not something anyone else sees, but they are something I can reach for when I’m making a work. Language is tangible and intangible.

MHM: What is the pace of your studio work? How does it compare to making a site-specific installation where you might have a deadline?

LM: All of my work is slow. I am a distance runner, and I often compare my studio process to distance running. I don’t go out and run a hundred miles in a day. Similarly, I don’t go into the studio and resolve anything in a week. But through a regular and steady process of making, the work reveals itself over time. I have learned to work well with deadlines and to use them as a way to change my pace, to try new things, and, ultimately, to embrace opportunities. When I don’t have a deadline, I’m still in the studio, but I’m able to take a slower and more winding path. This inefficient path has lots of benefits. As shows were cancelled and delayed during the pandemic, I was able to approach my work in a less hectic way, to deviate more freely from my plan with no deadline looming. As the world stood still in the most dreadful way, the stillness resulted in big revelations in my studio that may not have happened otherwise.

MHM: In regards to Architectural Feedback Loop, I’m really interested in the idea of a maximalist like yourself challenging yourself to contain this mode of expression within the confines of small scale. Any chance we’ll see more small works in the future?

LM: I hope so! I tend to end up making everything ginormous. It’s kind of my natural inclination. And once you set that expectation, people give you plenty of space to work in—I started getting opportunities to do bigger and bigger projects, and it’s been kind of hard to carve out time and space for smaller ones. Once I started doing the smaller, wall-based rope works, it seemed natural to work at a slightly smaller scale. These works have slowed me down in a really meaningful way that has also influenced the way I see my installations. I’ve even thought a bit about trying to make sculptures that are not installations…which is something I’ve never really done.

MHM: You’ve mentioned taking risks and letting go. Do you actively try to take risks or does it happen spontaneously? Is it important to you to not know what you’re doing?

LM: I think I do better work when I don’t know exactly what’s going to happen. Proficiency is dangerous. Once you know how to do something, it’s easy to just keep regurgitating the same thing. I try to be critical of my own process. It’s fun to throw myself a curve ball, to have something new to respond to. Sometimes, of course, this happens by accident, which is probably most exciting.

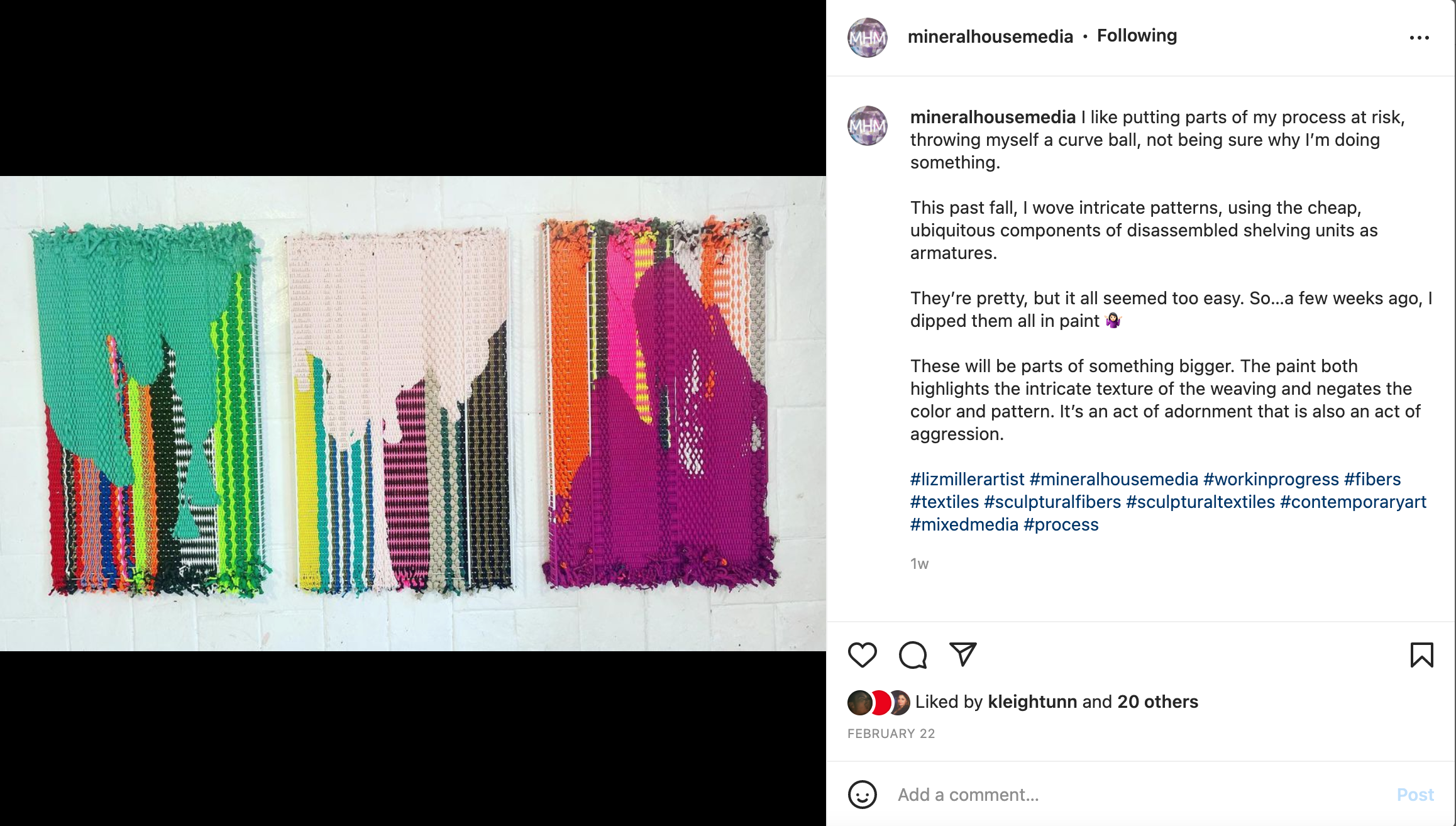

MHM: I’m thinking a lot about your recent experimentation with paint in your wall-based works. Paint is an additive material by nature, but it actually feels subtractive in selectively masking the detail and wide array of color and pattern within the rope fibers themselves. Can we expect to see more of this in future works? Are there any other new materials you’re considering adding into the mix?

LM: I’m so glad you noticed the subtractive quality of adding the paint to the woven textiles! It’s like I’m highlighting the history of the making, but also erasing it at the same time. I really didn’t know I was going to do this, but when I finished the textile components, they just looked complete in a way that I could not tolerate. Someone told me one of them was a beautiful weaving…and I knew there had to be an intervention. There was something so satisfying about taking all that labor…and just making it disappear into a puddle of paint!

I’ve definitely been playing with ways to integrate my background in painting with the recent works. I have undergraduate and graduate degrees in painting, despite the fact that I haven’t painted in any traditional sense of the word for many years.

MHM: What other artists are you looking at right now? Any books or music you are finding influential?

LM: There are so many great artists out there, it’s always hard to name only a few but I will say: Haegue Yang is a genius with materials, and Ebony G. Patterson has so many layers of conceptual information in work that is also seductive and beautiful.

I’ve been kind of enamored with the number of artists working in textiles and fibers who are doing extraordinary work. I think the recent Vitamin T: Threads and Textiles in Contemporary Art is a fabulous overview…

As far as music: I’ve been obsessed with two LA-based artists who make instrumental music: Mary Lattimore and Noveller. After so much news and so much talk, it just feels nice to disappear into a compelling soundscape for a bit, no lyrics needed.

Liz Miller’s work has been featured in solo and group exhibitions throughout the United States and abroad. Her awards include a McKnight Foundation Fellowship for Fiber Artists, a McKnight Foundation Fellowship for Visual Artists, a Joan Mitchell Foundation Painters & Sculptors Grant, and several Artist Initiative Grants from the Minnesota State Arts Board. Miller has completed residencies at Stove Works (Chattanooga, TN), the Joan Mitchell Center (New Orleans, LA), and the McColl Center for Art + Innovation (Charlotte, NC). Miller lives and works in Good Thunder, MN and is Professor of Installation Art and Drawing at Minnesota State University-Mankato.