Interview with Kelley Anne O'Brien

Interview with Kelley Anne O’Brien

June 2022 Digital Resident

A conversation with Clay, Olivia, & Larkin of Mineral House Media

“My practice focuses on the death and rebirth of natural and human-made ecosystems and social movements. I interrogate systems of control, while looking to create conversations with our past. My research-based practice takes the form of time-based media and installations to offer a glimpse into personal and collective experiences across spaces of heightened political importance. Through immersive installations, sound composition, and the integration of archival materials I emphasize overlaps of histories, environments, and time.

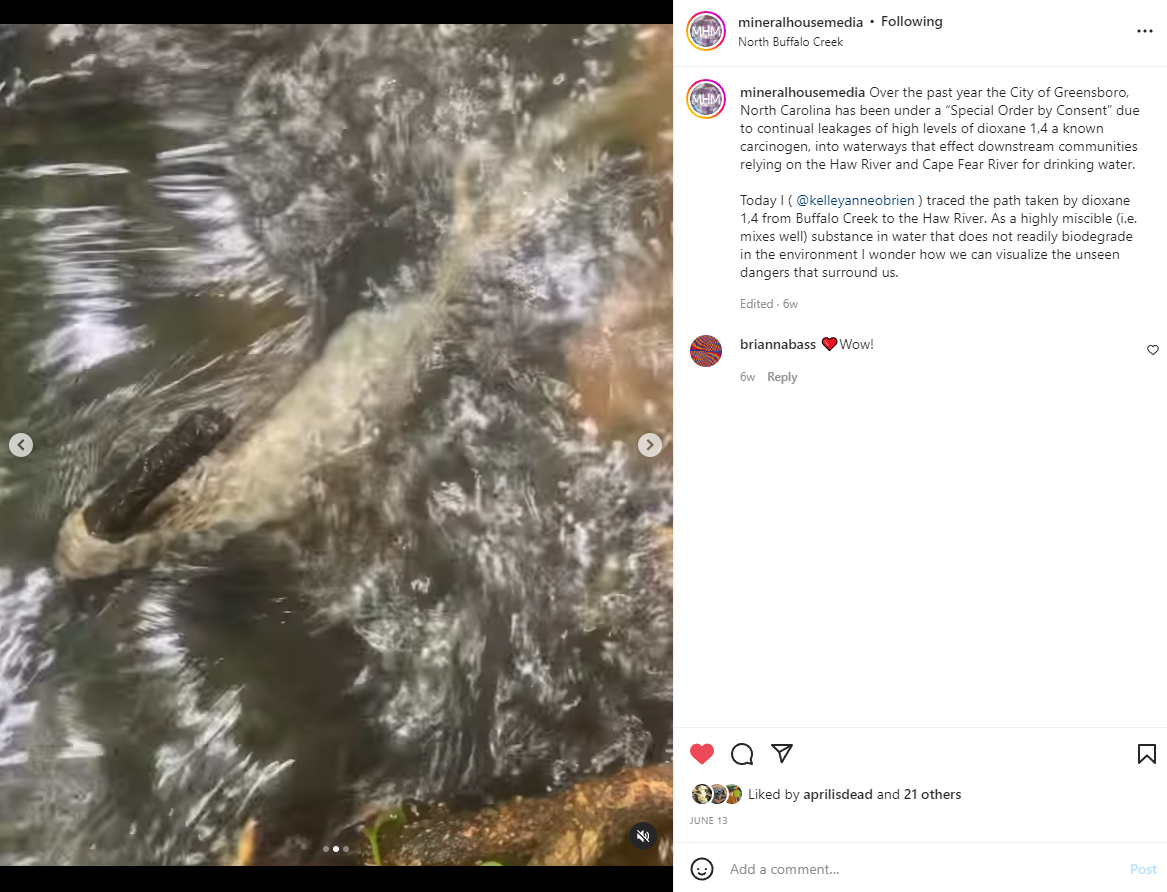

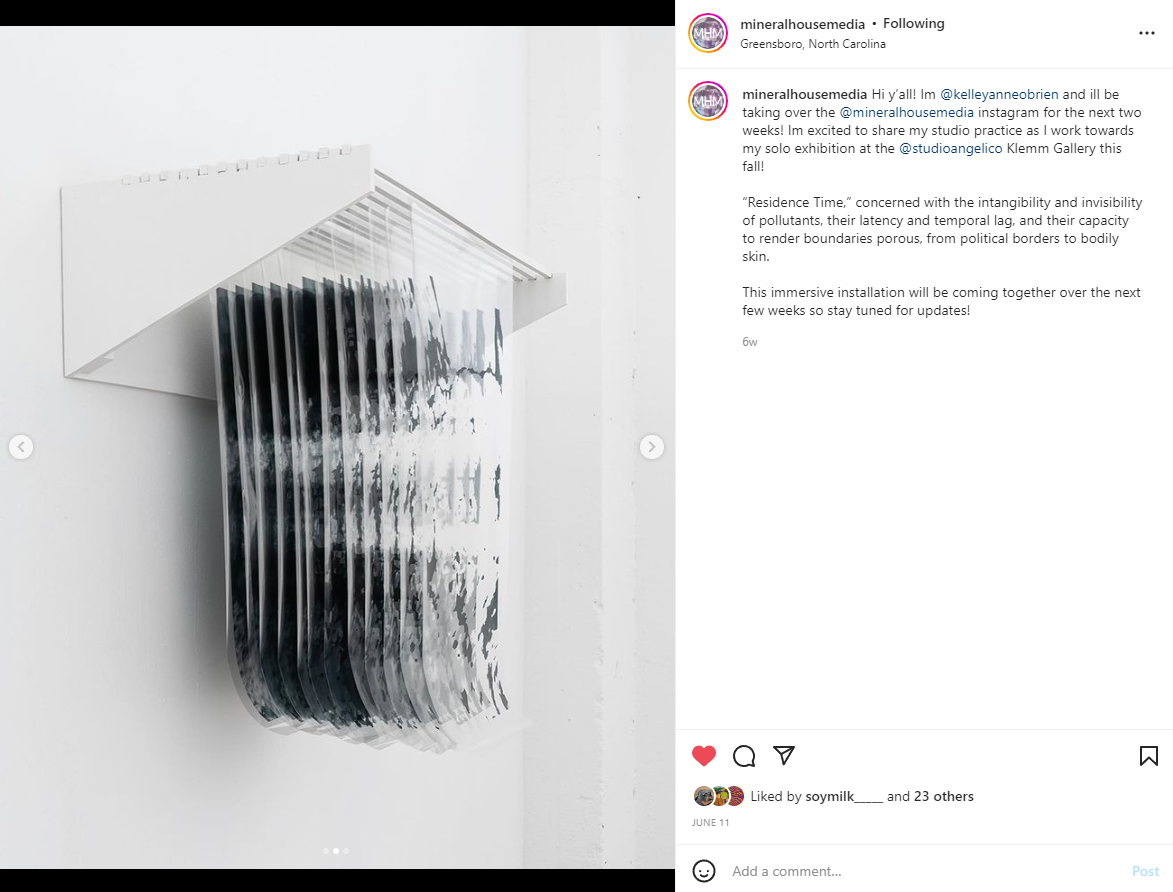

During the Mineral House Residency I will be experimenting and exploring new forms for my upcoming solo exhibition “Residence Time,” opening August 29th at Siena Heights University’s Klemm Gallery in Adrian, Michigan. "Residence Time" is an exploration of the Cape Fear River Basin runoff that threatens human and non-human life from Greensboro to the Atlantic Ocean and beyond. This multi-part installation documents the unseen, violence embedded in our drinking water, as the continual leakage of “1,4 dioxane” into the Cape Fear River basin contaminates the drinking water of over one million people. By overlapping social, environmental, and industrial concerns this installation links our bodily health to that of our river, specifically the chemicals present in our waterways which are infiltrating our blood streams, causing harm to both.

My interest in the contextualization of history and contemporary life through workshops and installations is an effort to establish a reciprocal relationship between ourselves and the environments we live in. I present history as fluid, responsive to lived experiences, influenced by memory and non-hierarchical. My perception of our world is influenced by feminist philosophies that are not restricted to the roles/thoughts of women, but rather are opportunities to rethink the dominant representational systems that traditionally have oppressed people, environments, and spaces. The effort to comprehend the present by highlighting what has been excluded from the conventional models of history stands in contrast to traditional authority and power. Through my art practice and on-going engagement with the communities in which I find myself, I ask how we can advocate for voices, issues, and concepts that have not had space prior.”

-Kelley Anne O’Brien

Mineral House Media: When did you know you wanted to be an artist, and how did you pursue it?

Kelley Anne O’Brien: I don’t think I ever knew that I wanted to be an artist. As an undergraduate architecture student I thought I was interested in designing spaces for human interaction but it turned out I was more interested in critically analyzing how the built environment shapes politics, ecosystems and behaviors. I went to graduate school for furniture design thinking that the smaller scale would allow me to explore these ideas further. As I struggled to figure out how to design things with conceptual intent I found myself creating unauthorized installations and performances across the city of Pontiac as a way to explore how design decisions led to bankruptcy; from there I became interested in creating new works that explore connections between systems of power and urban planning or lack thereof, in the Philippines and back in the United States in Cleveland. I think I still struggle with the idea of calling myself strictly an artist as I have no formal training and I’m more interested in overlaps of specialties rather than the divide.

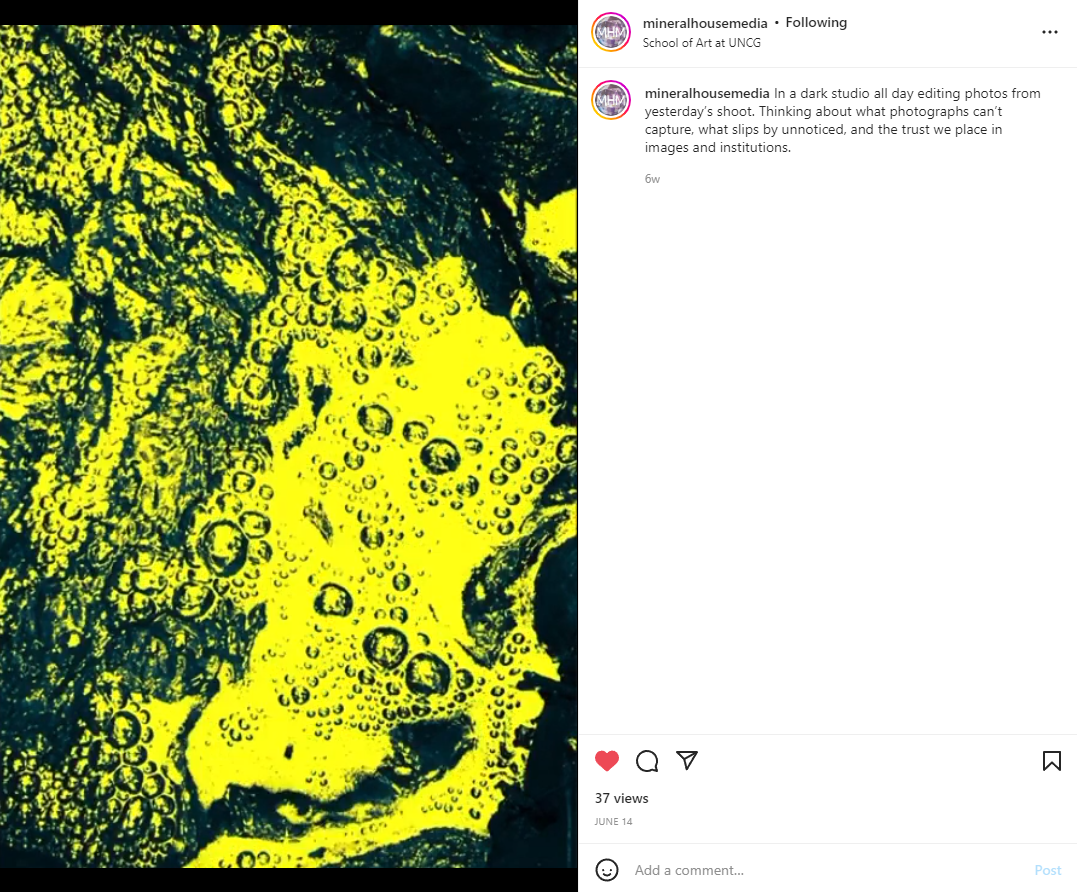

MHM: How do you approach the challenge of making work about the invisible?

KAO: In the past my art practice has been driven by dialogue, narrative and direct representations of the world around us. In this project I’ve challenged myself to make work about something that cannot be seen and move away from direct representations towards the abstract. This is a particular challenge for me as I’ve never worked in abstraction and don’t feel entirely comfortable with producing in this manner. So for most of this work I’ve started with direct representations such as images of polluted rivers and worked through heavy digital processing to remove the identifying characteristics hoping that these representations will allude to their origins without directly stating it.

MHM: Can you tell us a bit more of the Cape Fear River Basin runoff story? How did you get interested in this problem? How did you start your research into it?

KAO: I first got interested in the Cape Fear River basin when I moved to North Carolina. My practice often engages the places that I live as a way to orient myself within a new space. Often I start with the Wikipedia page for the city that I find myself living in and then from there I look for interesting or out of the ordinary situations to explore further and highlight some of the issues or solutions that make this community unique or different but also relate to more global concerns. My arrival in Greensboro coincided with one of the largest spills of dioxane 1,4 in the city’s history. I heard about it on the news and was super interested to learn more about why the city seemed to protect the industries over the individuals. From there it was all about asking why. Why would Greensboro not release the name of the company involved in the spill? Why was the spill allowed to happen? Why has this been an ongoing problem throughout our city’s history? How does it affect our residents and how does it affect the land?

MHM: How do you think about trust, betrayal, and danger in the context of your practice?

KAO: I think our relationships to our cities and our land depend on the sense of trust that has been constantly broken by those in power. The role of art practices can be to reveal the systems of power and the inequalities that result from a few wielding the most power. I think about my practice as a space to tell a story that is often too complex to be understood in its entirety. My art practice creates places where I can layer multiple related stories on top of each other to give the viewer a sense of the overwhelming complexity, danger and power in our communities. As we often all feel betrayed and on the verge of danger, we also have to trust in some way that our communities value our lives even when there is overwhelming evidence that this is not always the case.

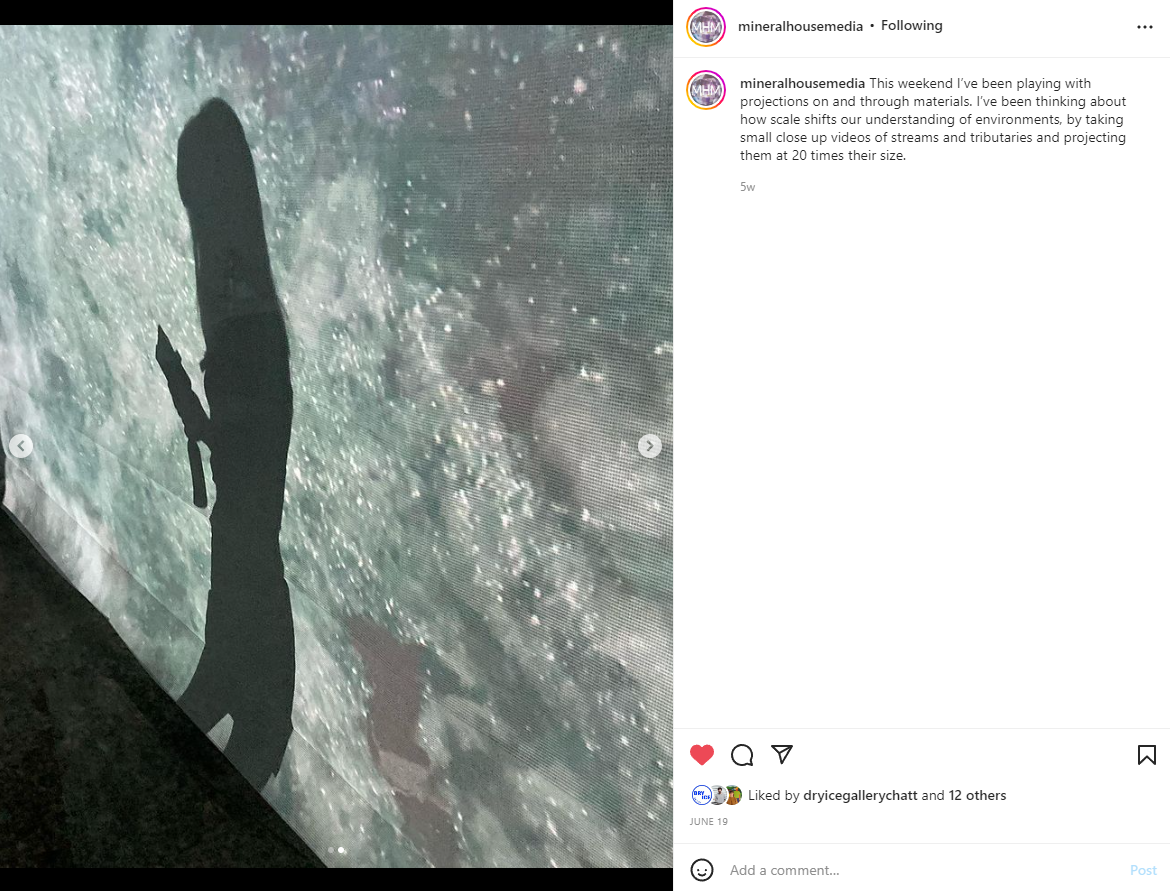

MHM: There is a definite parallel between your work in time-based art and the necessity of time in Nature. How did you arrive at making immersive and time-based installations? What draws you to this kind of making?

KAO: I came to making time based and immersive work through my roundabout journey as an artist. I’m educated as an architect and designer who felt that those worlds cannot accurately represent the systems of control and power that truly define our lives. I started making videos documenting performances and interventions in the town I lived in as a way to explore how my city had become bankrupt. These video documentations led me to making more narrative films which I’ve become very comfortable making. Over the past few years I’ve tried to challenge myself by removing narration for my projects allowing visual and physical imagery to drive the storytelling. From here I’ve also been interested in the way that we are surrounded and immersed within ecosystems (both man-made and “natural”)in a way that I think immersive installations mirror. Additionally, I’m really interested in the ability to control all aspects of someone’s interaction with the artwork through lighting, smell, sound, level of comfort and sight that only come with the immersive qualities of installations.

MHM: What artists are you looking at right now and how are they influencing your practice?

KAO: I truly love the collaborative projects by Janet Cardiff and George Miller, specifically the way they tell stories through narration and soundscapes defining space with speaker arrangements. They also seem quite interested in the overlaps of multiple narratives and histories that happen through our relationships to the environment, to architecture, to the past, and the present. Additionally I’m really excited about Sandra Perry’s use of digital technologies to explore themes of racialized violence, history, and the false vision of the democratization of the Internet.

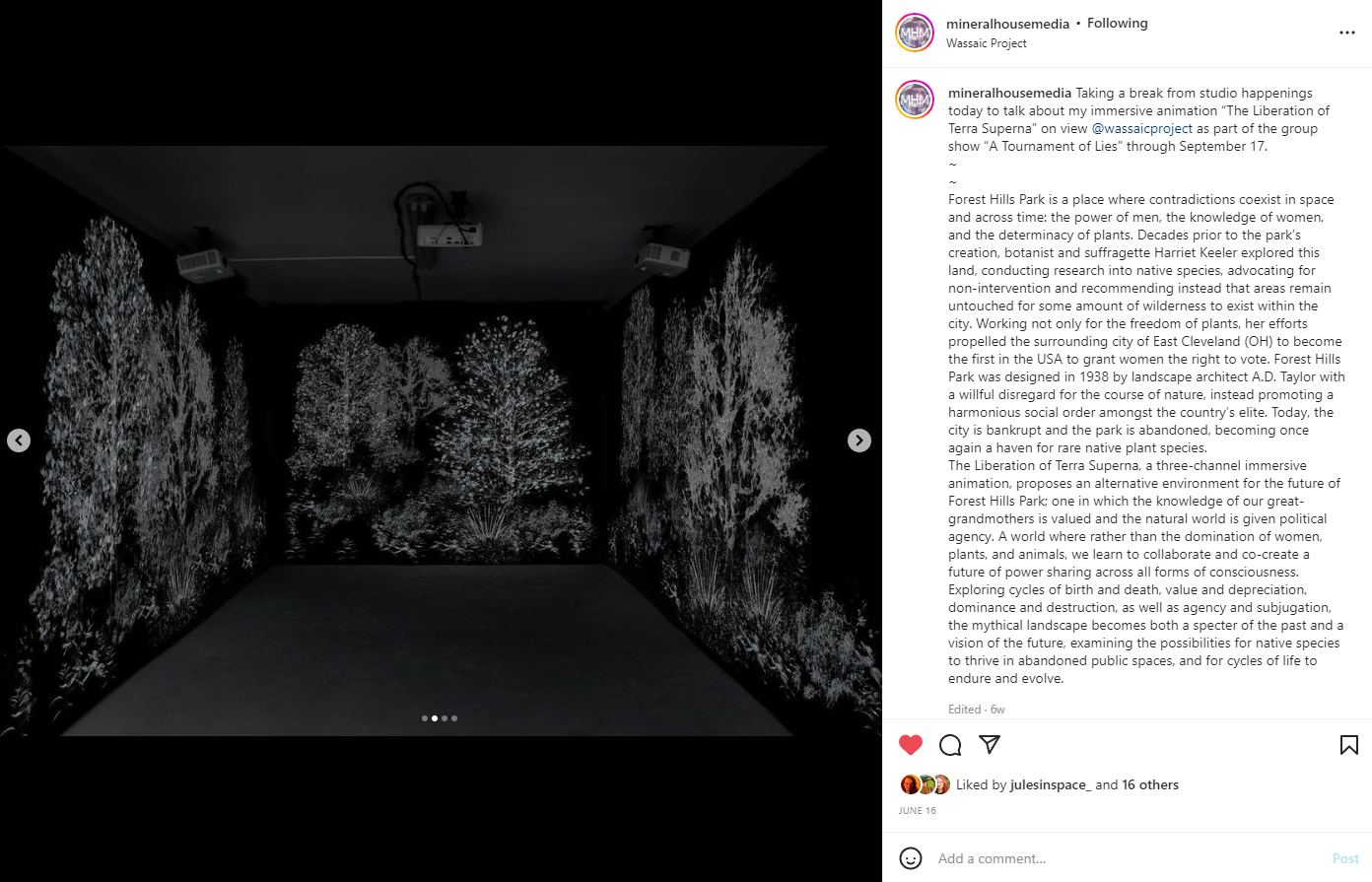

MHM: Can you tell us more about your interest in the Women’s Suffrage Movement in connection with nature? How did you first learn about Harriet Keeler?

KAO: My interest in the women’s suffrage movement extends from my interest in the history of Cleveland and East Cleveland. East Cleveland was a wealthy white suburb of Cleveland where Rockefeller had a summer home. It once had more millionaires per mile than anywhere else in the country. It was also the first place east of the Mississippi to allow women the right to vote. Upon looking deeper into the women’s suffrage movement in East Cleveland I discovered the history of Harriet Keeler. The first woman superintendent of schools, president of the local woman suffrage chapter, author, teacher, there was a lot to unpack about her work. I was particularly interested in the 14 volumes she wrote on NorthEast Ohio native plant life, in all of these books she advocated for untouched wilderness intermingled with the city. At the same time I was researching the park that used to be Rockefeller summer home. This park's contentious history as a place of wealth and then as a public park that would promote civic virtue filled with nonnative European plants became a site layered with history and metaphor. When thinking about the women’s suffrage movement the idea of women being told that their voices didn’t matter or more importantly perhaps they had no voice seems similar to many conversations we have now about the intentionality of plants. There are many arguments being made now for the agency of plants, for slowing down and listening to the needs and desires of plant life. One could argue that our environment and our cclimate are active participants in the political sphere. I’ve been really interested in thinking not about the divisions of the oppressed but the similarities, and opportunities to support each other's struggles. I see this narrative of the oppression of native plant life in favor of European varieties as a metaphor for the various forms of oppression and struggles for agency that continue throughout time. So all this work is about nature and the women’s suffrage movement but it's also much greater than that.

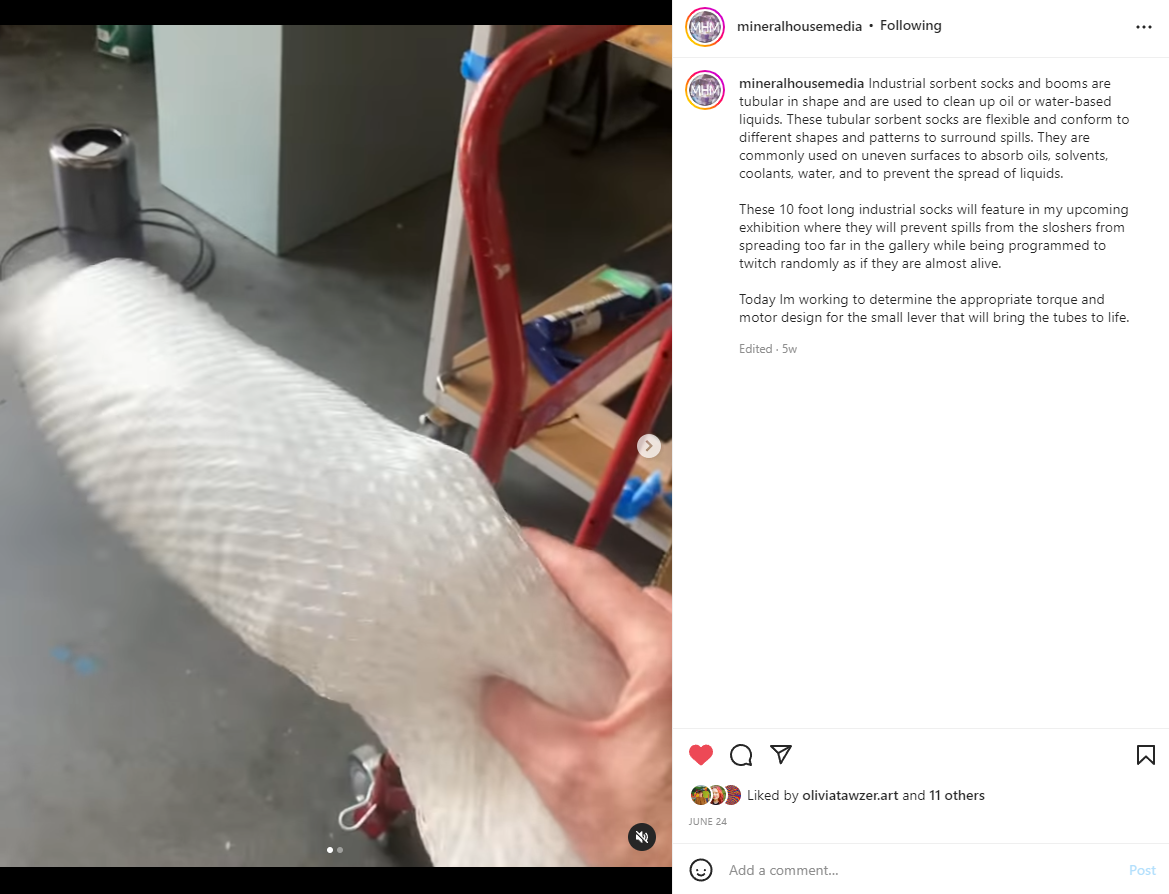

MHM: What made you decide to use automation in your work? What have been the challenges so far?

KAO: A lot of my work is driven first by the story and concept and then I discover what materials and methods and modes would best tell the narrative. For this project I was really interested in how the objects in the gallery could start to become individual actors with personality and intentionality. These small robots created with servo motors and Arduinos became the perfect solution for bringing these objects to life. I’ve encountered many challenges in making this work from waterproofing motors to coding and the numerous cords and power supplies that will be running through the gallery. I’ve been thankful to collaborate with an engineer who has the expertise that I lack. While hiding many of the motors I hope to acknowledge the cords and wires running through the gallery as tentacles connecting and grounding all the individual pieces.

MHM: How does collaboration with other people play a role in your practice? Specifically when you are creating a waterproof machine, like a slosher, or a distinct smell for a diffuser, such as the ‘dioxane 1,4’ scent?

KAO: I’m a huge promoter of the idea of collaboration specifically because as a conceptual artist each new body of work requires a new set of skills and it would be impossible for me to be an expert in all of these. I’m thankful to have made many connections with many musicians, engineers, chemists, welders, and computer programmers, who have helped me to bring my visions to life. Sometimes this collaboration is strictly about realizing my vision and other times he becomes more about the act of creating together. For this project I have worked with a perfume designer to create the scent of dioxane 1,4 based on the descriptions of scientists and chemists as we can’t smell it ourselves. This became quite a creative pursuit, to think about how people describe smells and how to translate that into a reality. So there was a lot of back-and-forth about what emotions and feelings to evoke and how to control the dispersion of the smell throughout the space. My collaboration with an engineer to create the slosher was more straightforward physics. I wanted a motor that would move quickly to splash the water and fit within certain dimensions and the engineer worked to meet those requirements. Additionally I’m working with a musician in which I described a feeling and environment and a sense of foreboding that I wanted them to make a soundtrack about. So I gave them a lot of words, a lot of feelings and a little bit of the story and asked them to create the soundtrack and send me the individual isolated tracks which would become the foundation for an abstract projection that I would create. In this way I was letting the creative pursuits of my collaborator determine my output as opposed to my creative work determining their sounds.This particularly has been a new and exciting way to work with a collaborator as it has forced me to think outside of my normal ways of making to arrive at an expected results.

MHM: Have you received any advice/inspiration that has helped you along the way?

KAO: I think the best advice I got was basically just to make friends and nurture relationships with as many artists as possible. You never know when those friendships will turn into collaborations or opportunities to support each other‘s growth. Specifically one of my friends that I’ve known since graduate school, our friendship and relationship has actually grown and become more meaningful after school. We were casual friends during graduate school but it wasn’t until a few years later when she called me for advice that we actually started speaking on a somewhat regular basis. That relationship had intensified over the years and she came to support and help me put together an exhibition at the gallery I ran and then she curated an exhibition of mine and currently we write letters of support and recommendation for each other on a regular basis. I think graduate school me would be surprised at the extent of our relationship and how it’s really flourished over the years. That this wasn’t a friendship that I imagined would become so meaningful in my life. So I think it’s important for other artists to see the idea of networking not as a cringy business tactic but rather an opportunity to build friendships and communities of support throughout your career.

MHM: What/who is most influencing you right now? (i.e. books, artists, colors, podcasts, music, etc.)

KAO: Currently I’m really excited about the book Entangled Life by Merlin Sheldrake which explores relationships between fungi and humans and discusses Merlin’s research in tropical forests of Panama, where he explored incredible links between mushrooms and the ecosystem and human health. I’m particularly interested in this idea of interspecies connections, communication, and support. Additionally, the podcast All My Relations hosted by Matika Wilbur Adrian Keene and Desi Small-Rodriguez discusses indigenous ways of relating between social issues, tribal, global and ecological concerns emphasizing the relationships between indigenous people, their lands ,and spirituality in the contemporary world. I’m also incredibly excited by the work of Zheng Bo and his social/ecologically engaged a practice where he attempts to de-emphasize a human centric worldview to strive for interconnectedness between all beings. His commitment to all inclusive multi species relationships in which he learns from biology and study of plants to create daily rituals that focus on interspecies care. I’m particularly interested in trying to expand my worldview to one that emphasizes connection relations and collaboration with other humans, other animals, plants and fungi and there’s so many artists, activists and theorists working to expand this view through many fields.

Kelley O’Brien is an interdisciplinary artist working in the American South. With her background in architecture and design she negotiates boundaries between industrial and “natural” landscapes, through a feminist perspective, to explore cultural links between gender hierarchy and the domination of the natural world.

She has exhibited at the CICA Museum (Korea), National College of Art and Design (Ireland), Stroboskop Art Space (Warsaw) as well as Transformer Station, McDonough Museum of Art and The Everson Museum of Art in the United States. Kelley has been awarded grants from the Foundation for Contemporary Arts, Ohio Arts Council, Wexford Arts Council, and a Fulbright Scholarship to the Philippines and attended residencies at Green Papaya Art Space in the Philippines, the Irish Museum of Art in Dublin, Laboratory Spokane, Wassaic Project, and the Scottish Sculpture Workshop in Lumsden.

Her artistic practice extends into her academic and curatorial research through collaborative projects with Francis Halsall under the title “Mapping Systems.” Collectively they have held workshops, lecture courses, and curated residencies in Ireland, the United States and the Philippines. Through her art, curatorial, and collaborative research practices, O’Brien seeks to highlight precarious and indeterminate environments as a political act to give power to untold histories and providing underrepresented perspectives as alternative ways to critically engage with our ecosystems locally and globally.