Interview with Cherish Marquez

Interview with

Cherish Marquez

May 2021 Digital Resident

“Cherish Marquez (she/her) builds complex imaginary worlds through interactive animation and game design. Her work explores environmental justice, mysticism, mental health, and queer identities, and healing from generational trauma. She puts marginalized experiences in the center of her work. She calls attention to issues of immigration and oppression by incorporating sociopolitical symbolism and the environment. Her work has a focus on the deconstruction of colonialism which is projected through religion, such as Catholicism. She does this by deconstructing physical objects and turning them into new symbols that represent her identity. Her work operates from a queer Latinx perspective and is heavily subjected to speculative futurism, which combines cultural practices of healing (Curanderismo) and technology to heal the earth of its trauma that technology has often caused (mining, nuclear power, etc.). She advocates against environmental racism and is inspired by the desert that she comes from. She works as an interdisciplinary artist, that delves into science, theory, and research. She combines the digital world with the physical world, often including handmade objects that act as interfaces to control the worlds she fabricates. She creates physical artifacts that contain the digital worlds she creates.

Her work acts as the mediation between digital and physical spaces, hoping to bridge the gap from her cultural upbringings to her study in technology. She creates a magic that is felt through her work which oftentimes is echoed through surrealist landscapes and animations that confront the viewer. Her work reflects on the corporeality between the physical and the metaphysical, allowing the viewer to navigate through a fictional landscape of uncanny beauty, danger, redemption, and the unknown. She also has experience in digital fabrication, creative coding, and wearables. Within all of these different mediums, her work is recognized through her unique designs that carry her personality and message throughout her work. Cherish Marquez challenges the viewer in questioning their connection with themselves and the world around them. She is hoping to guide the viewer to acknowledge the relationships we have with the natural world and the digital world. She strives to create accessible art and experiences that can be experienced by all, regardless of socioeconomic status, privilege, and ability.”

-Cherish Marquez

Mineral House Media: How do you compose your audio/sound design? Is it created all from scratch or pulled from other sources?

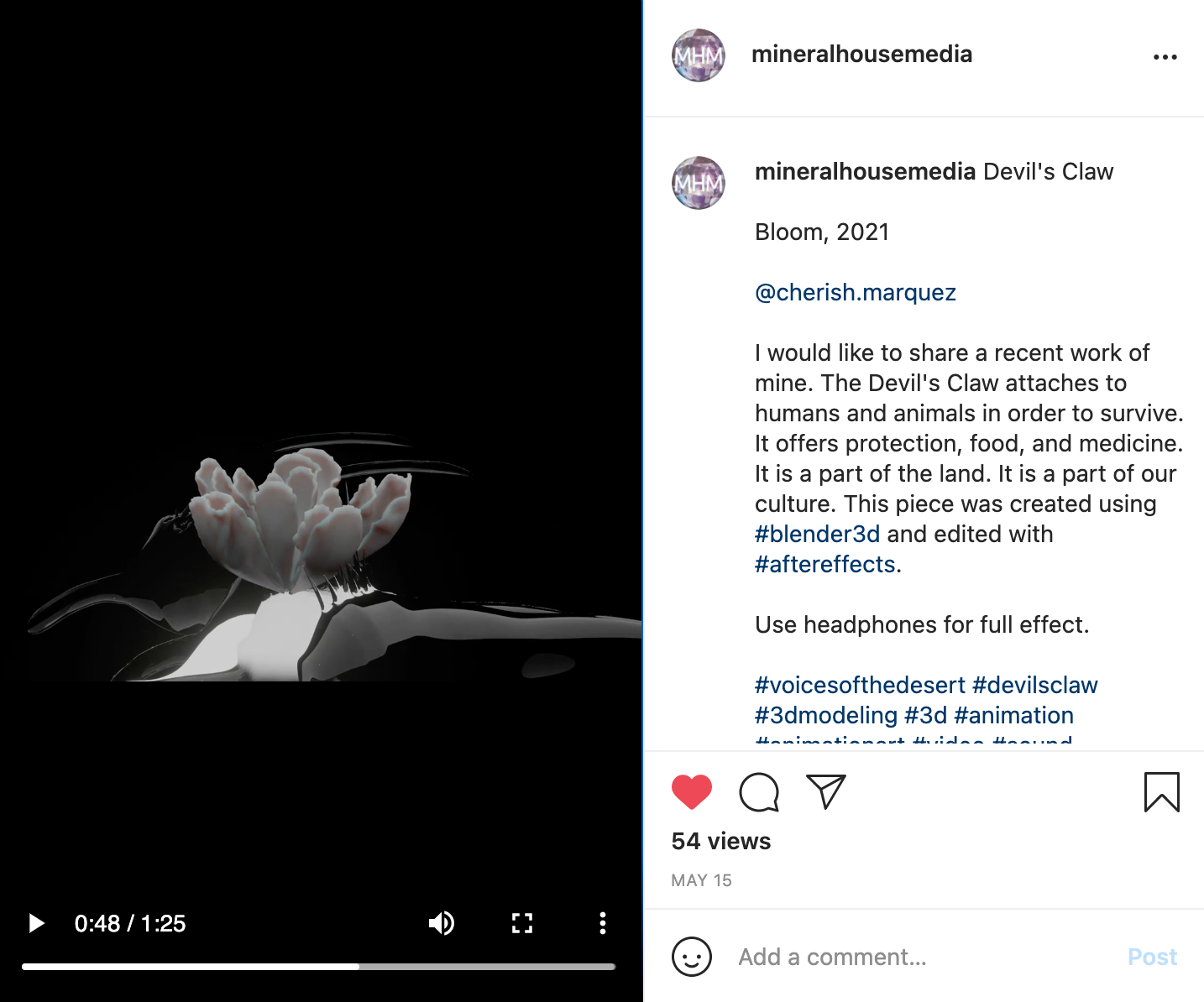

Cherish Marquez: I create my audio and sound design using sounds that I make physically, recorded sounds in nature, and various instruments. Most of my sounds are made from scratch; however, I pull from other sources when I need filler background noises. I distort the sounds heavily so that most of the sounds are made by my body and voice. For example, for Devil’s Claw I made some of the sounds by clicking my tongue and pushing the air out of my mouth making a rolled “r” whisper sound.

Devil's Claw, Digital Media, 2021

MHM: In Devil’s Claw, you mention it attaches itself to living creatures to survive. Can you share some more thoughts on this sort of parasitic relationship? Specifically how, instead of causing disease, it offers protection and resources to help aid its host.

CM: The Devil’s Claw is a desert plant that utilizes humans and animals in order to propagate by attaching itself to feet, hooves, and fur. In my culture when the Devil’s Claw dries out and the seed pods have been distributed, it provides spiritual protection from evil spirits. It is placed on altars, hung from car mirrors, and is placed in homes. Before it ripens it is edible and can be steamed like okra. It also has been used in basket weaving. Instead of viewing the Devil’s Claw as a parasite, I look at the plant as being resourceful and resilient. Using different species that invade its space in order to survive while also providing sustenance and protection.

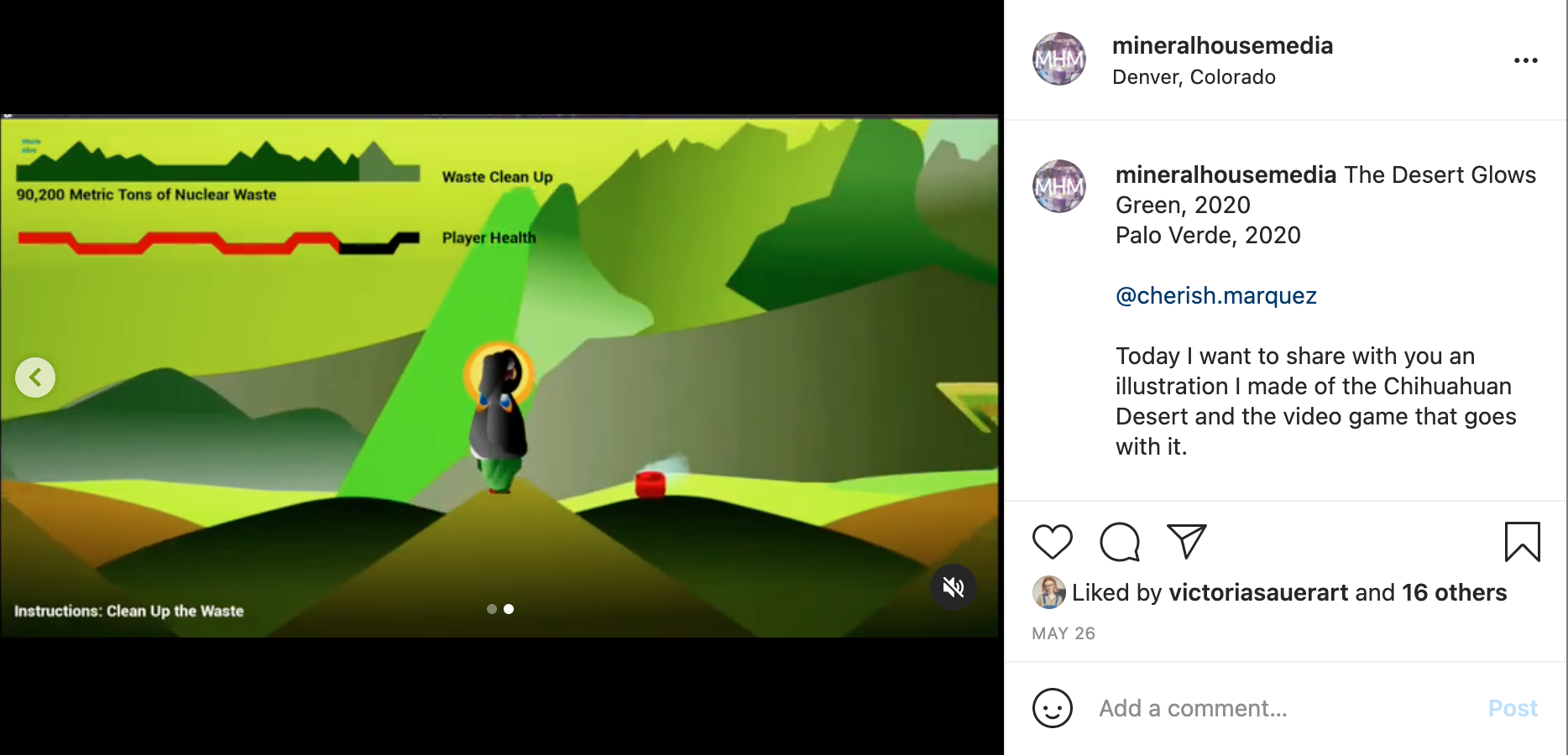

MHM: I love that you have implemented such essential teachable moments within the plot of your video games. To what extent do you consider the relationship between audience interaction, the visual experience, and these influential lessons on environmentalism?

CM: I consider all of the above! In game design, the creator must think about how the player is interacting with the game. I think about the mechanics of the game and how they relate to the overall message. For instance my game Palo Verde’s game mechanics require the player to collect nuclear waste in order to clean up the earth. The health bar and the clean up bar on the left indicate their progress. When nuclear waste is collected the player’s health decreases. With this particular game the player is immersed in the visuals and the overall lesson being taught as they play.

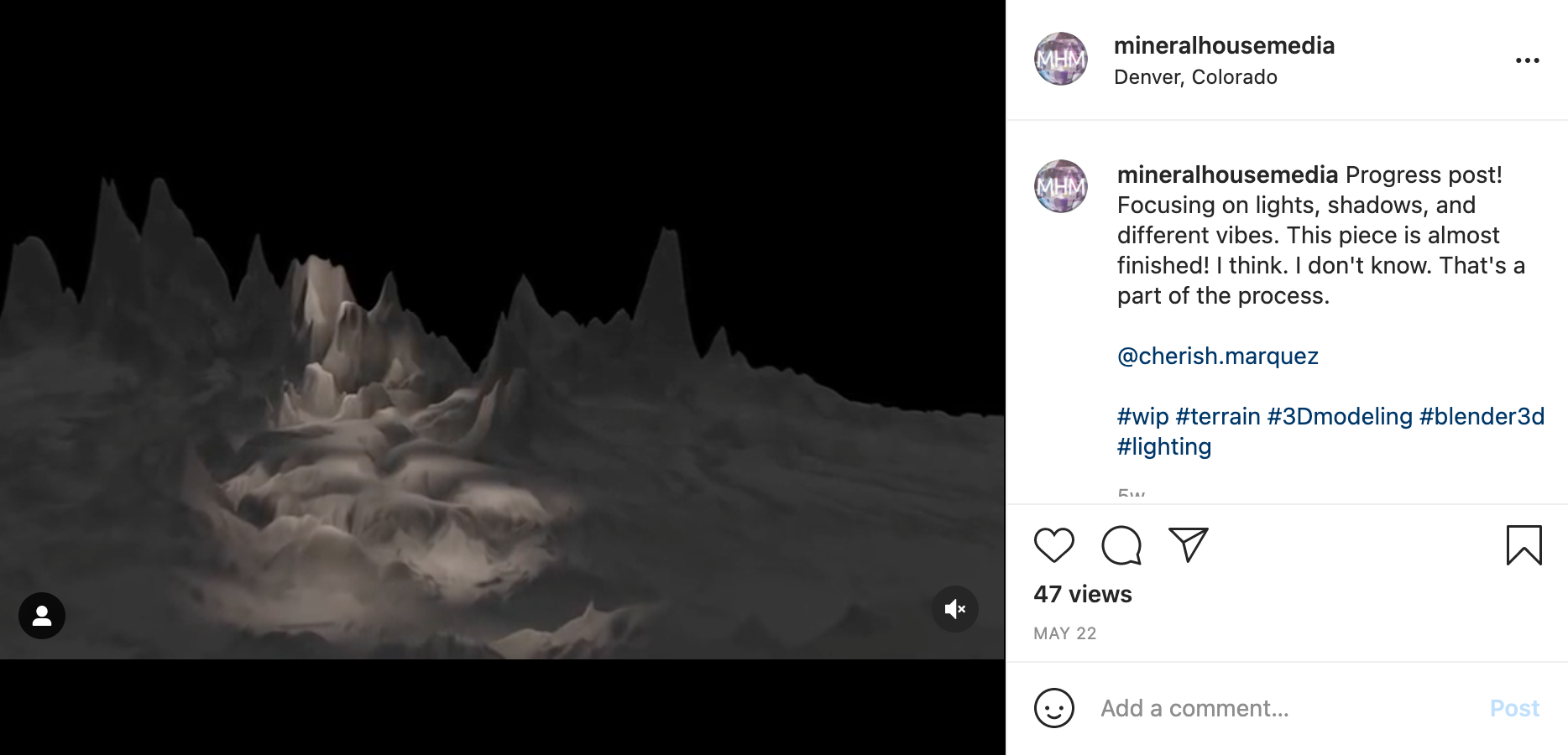

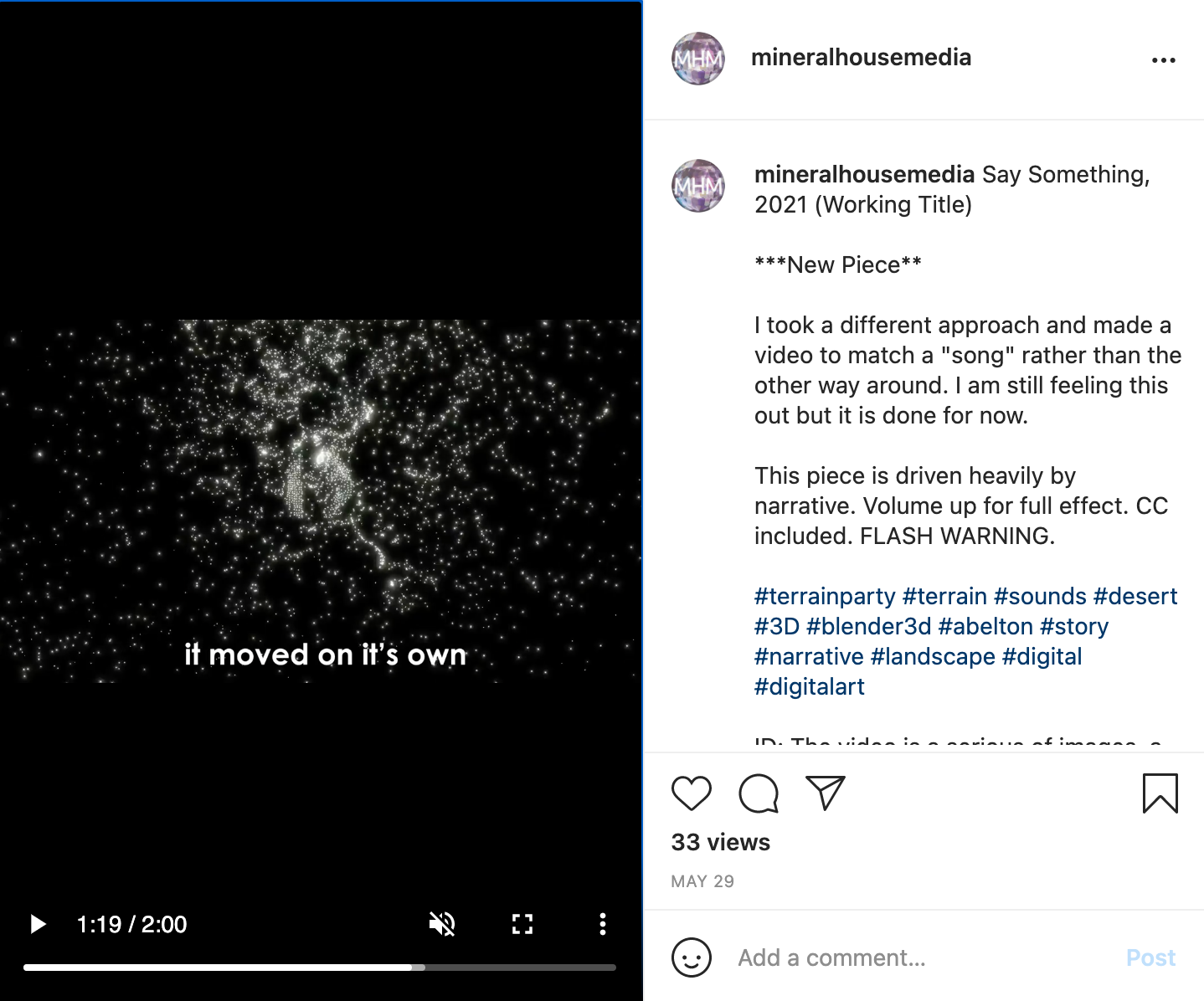

MHM: The mountains in some of your works share visual forms with sonic or scientific data. Your colors are delicate and otherworldly, the light can be warm and golden, or deep and haunting. What is your process for generating and designing these environments?

CM: My process for creating digital environments consists of representations of memories. I create safe spaces with bright and inviting colors but also spaces that feel uncomfortable. I focus on the ebbs and flows of emotions that we as humans experience and think about the physiological implications of these environments as they appear. Oftentimes I use color theory to dictate how I design things. I think about the sounds I use as colors. There is an innate representation of colors and emotions that we all have. I try to tap into that based on my own experiences.

MHM: How far are you aiming to take the appearance of your unconventional video game controllers? Do you think of them as unique sculptural pieces in their own right? Where do design and functionality intersect?

CM: I see my fabricated video game controllers as an object that bridges the mental and physical gap between the player and the video game. I want the controllers to represent an aspect of the game in order to bring the digital out into the physical while also existing as its own object, whether it be sculptural or wearable. I do this also to engage viewers that are not familiar with playing video games. The controllers I create are meant to simplify control rather than using a mouse and keyboard.

MHM: What do you imagine the theoretical convergence between our physical reality and technologically augmented reality (AR) to look like in daily life? What are its pros? Does it pose any risks?

“It is up to us to use that technology to aid the planet and ourselves rather than destroy it.”

CM: Unless there is a worldwide shift, technology will remain a part of our lives. It is up to us to use that technology to aid the planet and ourselves rather than destroy it. More specifically the technology we use daily, such as computers and cell phones. Augmented Reality for me is a way to insert ourselves into physical spaces. Such as, the Movers & Shakers company who created an augmented reality app Kinfolk that places historical Black figures as AR sculptures to replace the statues of Confederate leaders that exist. They did this to teach Black History using AR and so that young folx of color could see themselves as a part of our history rather than being excluded from it.

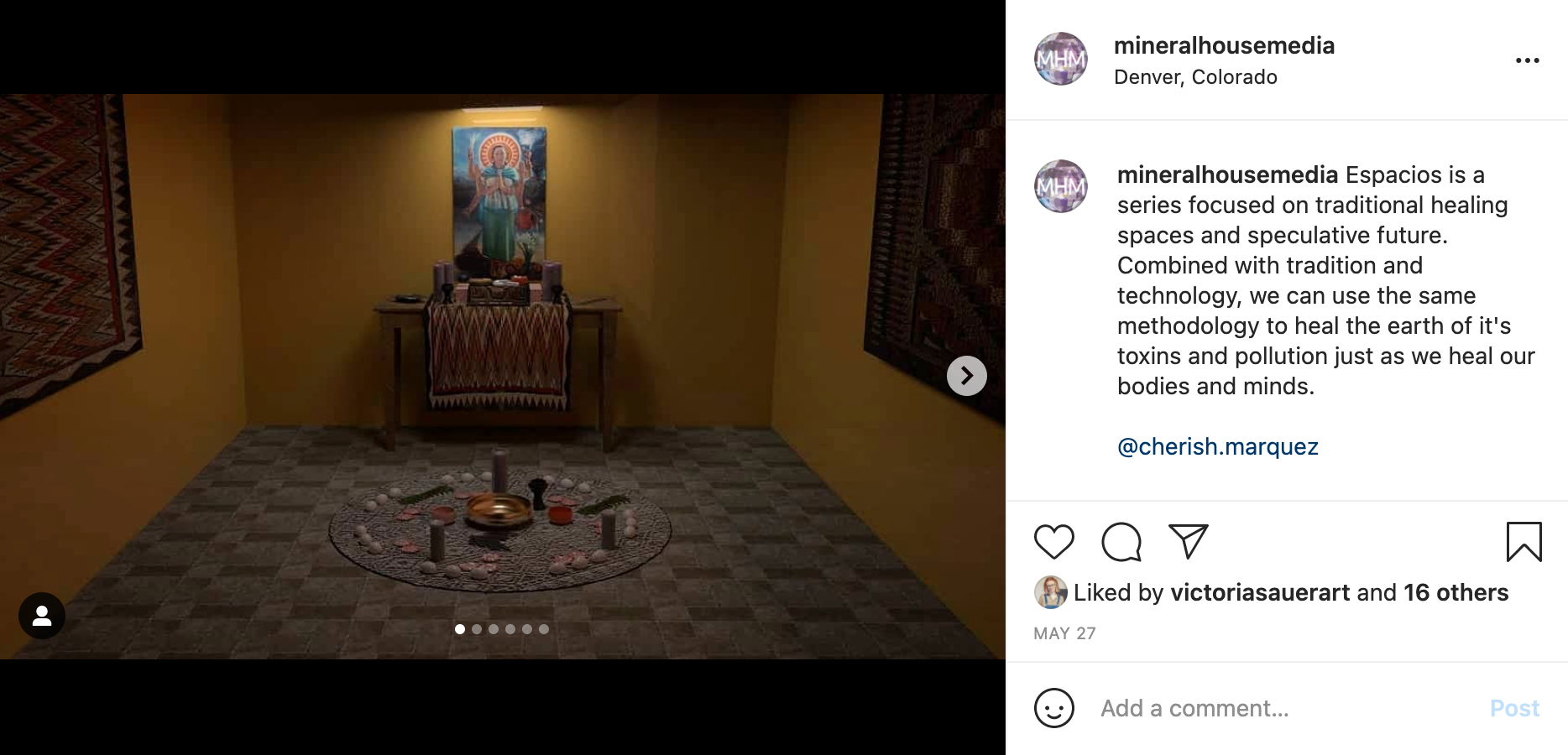

MHM: Has your experience interpreting the sacred and ritual in digital spaces influenced or altered your practice in a tactile sense?

CM: Not entirely. When engaging in ceremonial practices I focus on healing my body and mind and remove any barriers that are caused by negative energy to exist. I try to find a balance within the physical and the digital space. The most frustrating for me is the disconnect that exists between these two spaces. I aim to make immersive animations in order to bridge that gap.

MHM: Could you tell us a bit more about speculative futurism as it speaks to your conceptual approach and practical execution?

CM: I started to explore these rituals in order to theorize a speculative future where these objects exist and construct physical objects as well. For example, I created a speculative Radiation Dirt detector that one would wear on their arm and use to test the dirt for radiation. If radiation is detected they would use the Limpia Egg in order to cleanse the air and land of radiation so that it may be occupied again. All of this is purely speculative but ideas that we may need to consider in order to survive on the land that once provided us substance and heal it from the trauma that has occurred.

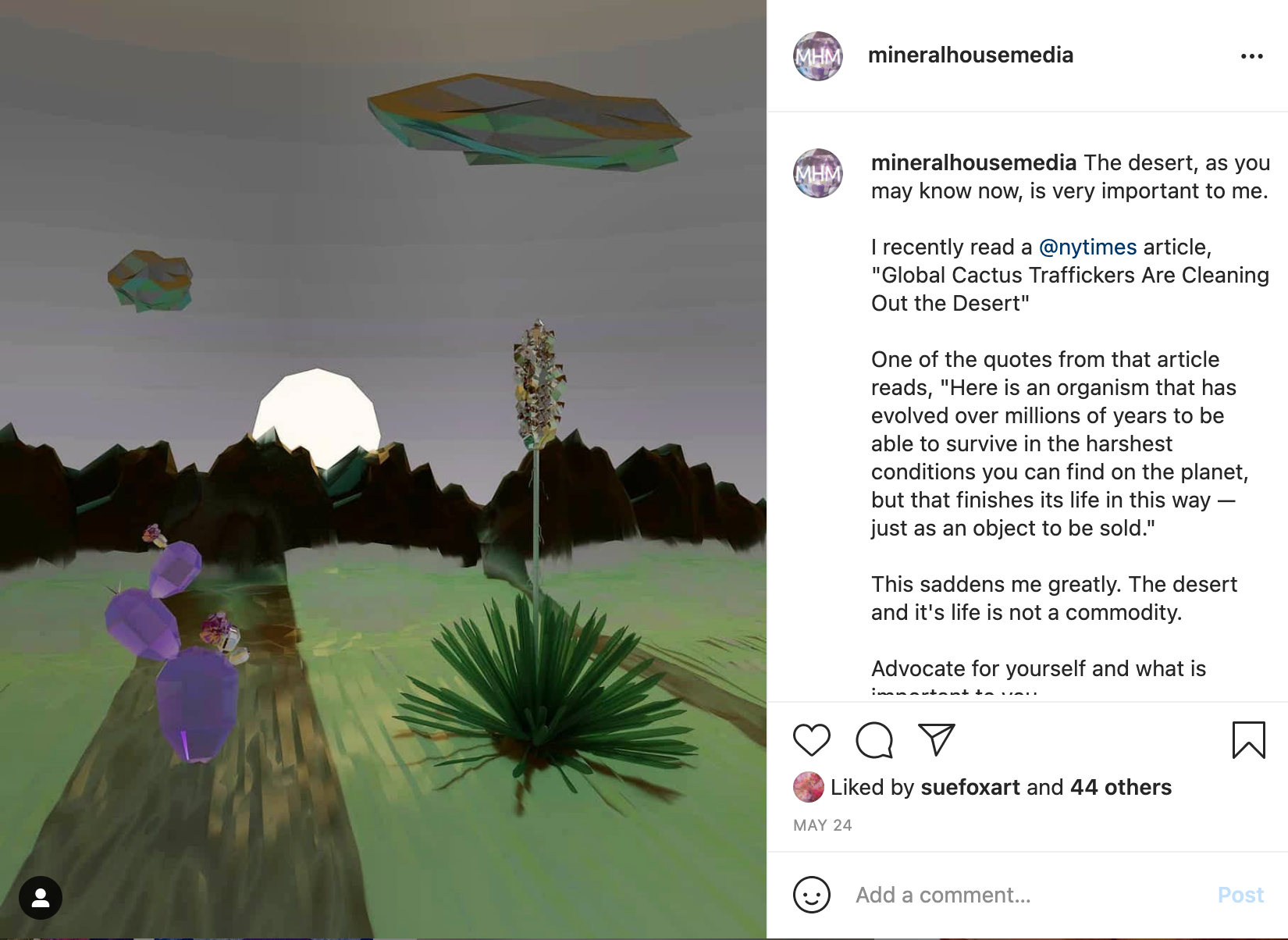

MHM: What inspires you most about the desert, both physically and metaphysically?

CM: I am from the small town of Sierra Blanca, Texas. It is a town that is surrounded by a vast landscape of dirt, rocks, plants, and mountains. The connection I feel is almost indescribable. I feel it deep within my chest, it’s comforting, emotional, and safe. When these ecosystems are interrupted it can cause a disconnect. The desert is vast and when I look out into it I get lost and feel metaphysical power within. The plants inspire me. Plants such as cactuses have evolved and continue to evolve in order to survive in the harsh terrain and can live long life spans. The plants represent resilience. Life in the desert grows despite the challenges it might face and while doing that also give back to the people around it by providing food and materials for clothing.

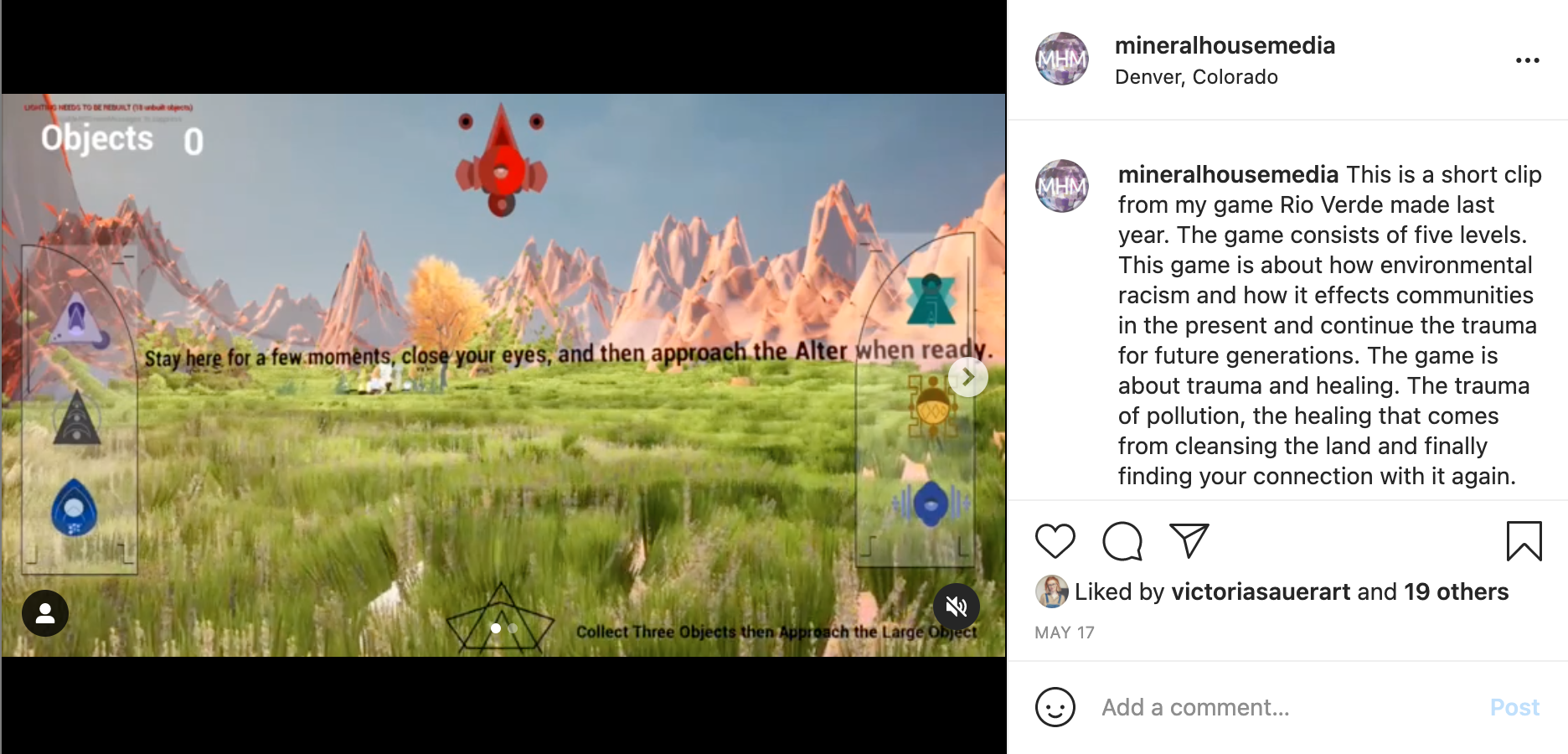

MHM: You tell an amazing story of how, through activism, your hometown stopped the Texas government from dumping nuclear waste nearby. How did this event inform/inspire your game Rio Verde?

“The desert is a sacred place that contains our memories, our ancestors, and our sustenance.”

CM: My experience with environmental racism influenced the game Rio Verde in that I saw the land as being hurt and abused. I wanted the player to see that the terrain was reaching out for help and in order to heal it you had to heal it by using technology that was inspired by vulture ceremonies. It is important to me to educate the players on injustice but also how my culture heals ourselves through these tragedies. I want to share these experiences because it is important to me to honor my ancestors and their practices by making them seen. The desert is a sacred place that contains our memories, our ancestors, and our sustenance. I wanted to show how important the land is to me and my connection. I felt that if I were able to ground the player they would experience a little bit of that too.

MHM: Why do you feel that the interactive digital worlds you create are the best medium for sharing marginalized experiences and engaging people of all abilities and backgrounds with the art world?

“Technology is accessible to those with the privilege to experience it.”

CM: Video games have always been exclusive to those who occupy marginalized identities. I have chosen to take back the digital space as my own. I grew up playing in these imaginary worlds full of challenges and complex stories. I realized that I was not welcomed in these spaces and had to prove myself. Through this medium I wanted to tell my own story through experience. I went from trying to exemplify empathy to giving the player responsibility. In my animation work I feel that it is important to have visuals and sound that work together to tell the story but can exist on their own without each other so that people who are Deaf or hard of hearing, and visually impaired can have the same experience. Technology is accessible to those with the privilege to experience it. I feel that it is important to reach out to as many people as possible digitally. So that whether you experience the piece in person, on your computer, or phone, the message is there.

MHM: What have you read lately that has informed or inspired your work? Are there any texts, films, or other media that are significant to your thinking about queer latinx experience, generational trauma, or environmental racism?

CM: Literature that inspires my work are Slow Violence and the Environmentalism of The Poor, written by Rob Nixon, Polluted Promises written by Melissa Checker, Dumping on Minorities written by Lauren Tarshis, Cleansing Rites of Curanderismo: Limpias Espirituales of Ancient Mesoamerican Shamas by Erika Buenaflor, Woman Who Glows in the Dark: A Curandera Reveals Traditional Aztec Secrets of Physical and Spiritual Health by Elena Avila and Joy Parker, Voices From the Ancestors: Xicanx and Latinx Spiritual Expressions and Healing Practices by Laura Perez, Fragments of Trauma and The Social Production of Suffering by Michael O’Loughlin and Marilyn Charles, Human Rights at The Crossroads by Mark Goodale, Voices From the Ancestors: Xicanx and Latinx Spiritual Expressions and Healing Practices by Maria Elena Fernandez, Playing With Feelings: Video Games and Affect by Aubrey Anable, Video Games Have Always Been Queer by Bonnie Ruberg, Woke Gaming by Kishonna L. Gray and David J. Leonard, Feminism in Play by Kishonna L. Gray, Gerald Voorhees, and Emma Vossen, The Assimilated Cuban’s Guide to Quantum Santeria by, Carlos Hernandez, Octavia’s Brood: Science Fiction Stories From Social Justice Movements edited by Adriennne Maree Brown and Walidah Imarsha, Atomix Aztek by Sessha Foster, Crash Override, by Zoe Quinn, and finally Borderlands La Frontera: The New Mestiza by Gloria Anzaldua.

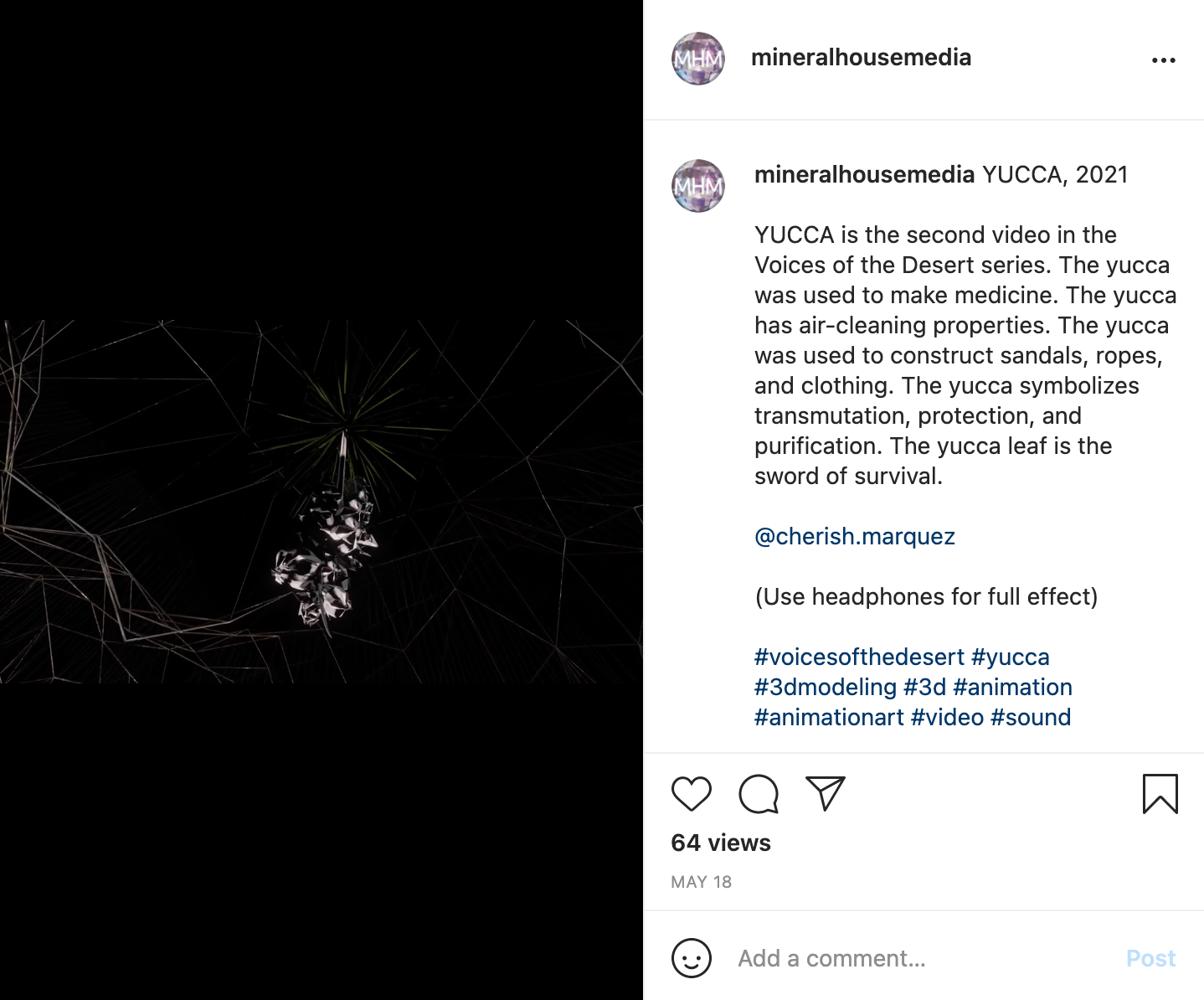

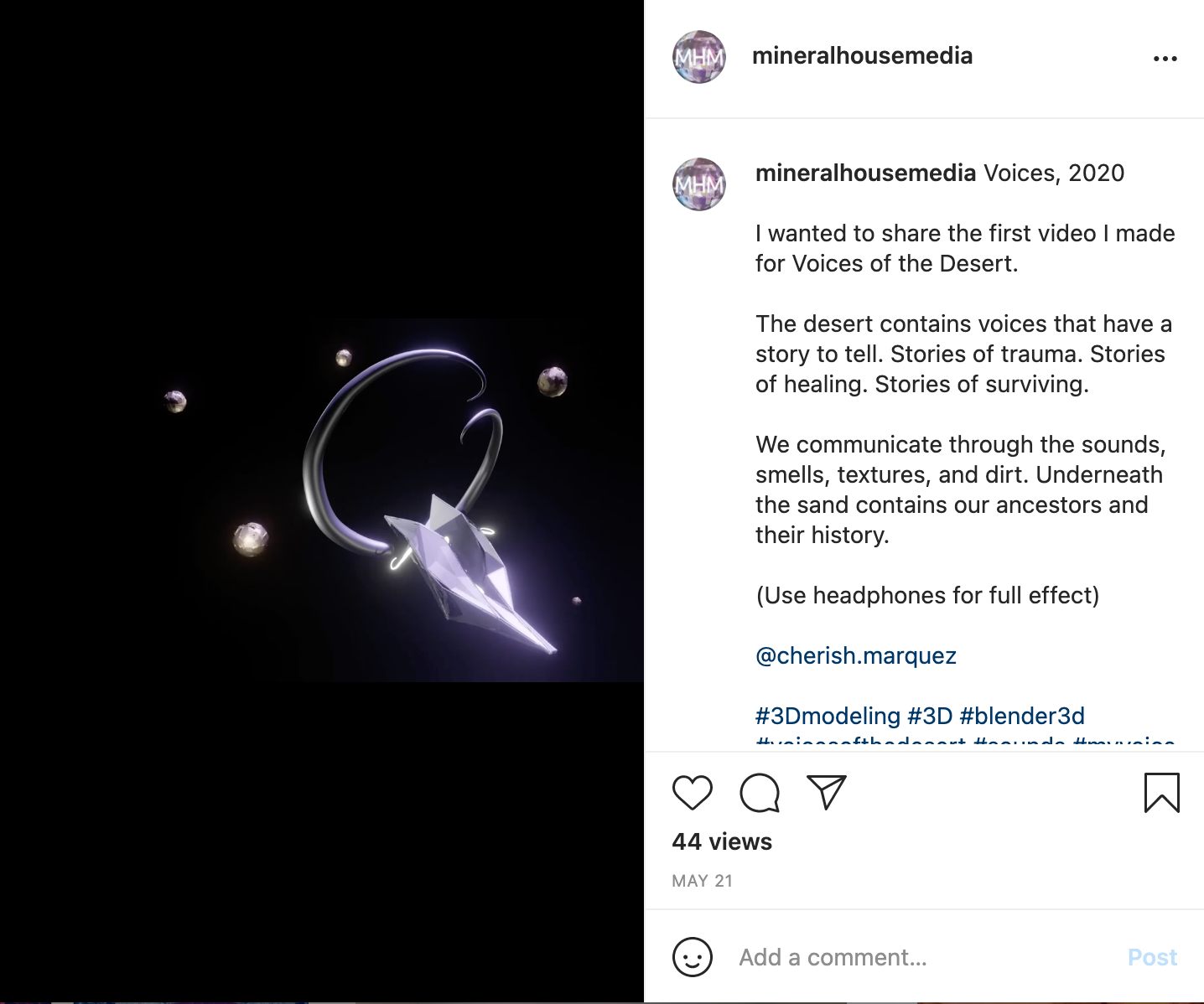

Yucca Seeds, Digital Media, 2021

MHM: Are there any new technologies or methods you would like to try working with?

CM: I would like to start working more with Raspberry Pis in order to create sustainable and accessible games that live as artifacts and that are powered using its own resources. I would like to make these out of recycled materials or materials that are biodegradable to balance out the technology that is being used within the object. I would like to start incorporating plant life and other biological beings so that they can not only survive but thrive off of technology. I am working to create installations that coincide with my animations so that the viewer can have a completely holistic experience. I have so many things to say and so many things that I want to do. My main goal is to find focus and intention within each of these ideas instead of overwhelming the viewer. I want to move the technical in the physical and push the boundaries of technology.

MHM: Are there any artists who address issues of queer experience, generational trauma, and environmental racism in ways that inspire you?

CM: Some of the artists that I admire are Cannupa Hanska Luger, a New Mexico based artist, who focuses on Indigenous people’s values, separated from the lens of colonialism. KITE is another indigenous artist working in multi-mediums. Kent Monkman is a queer indigenous artist who places himself into what are seemingly classic western paintings. His depictions are of a queer savior decolonizing the land. Virgil Ortiz is an ingenious artist who practices Indigenous Futurisms. Latoya Ruby Frasier is an artist exploring environmental racism in low-income urban communities through photography. Other artists that I have admired are Auriea Harvey, E. Jane, Elizabeth LaPensee, Guillermo Galindo, Anna Anthropy, Tabita Rezaire, Jeremy Bailey, Curanderas Transformando Guatemala, Curanderas: Maya Women Resisting Violence Through Theater and Performance. Some indie games are Crosser; La Migra; Seeds of Solitude by Rafael Fajardo, How Do You Do It? by Nina Freeman, Luxuria Superbia by Tale of Tales, Hair Nah by Momo Pixel, Keep Me Occupied by Anna Anthropy, Borders by Gonzzink, Like Roots in the Soil by Spacebackyard, Depression Quest by Zoe Quinn, and Thunderbird Strike by Elizabeth LaPensee. There are so many artists and game developers! I wish I could name them all.

Cherish Marquez (b.1989 El Paso, TX, USA) spent her childhood in Sierra Blanca, TX, and adult life in Las Cruces, NM. Currently, she lives and works in Denver, Colorado. She holds a BA in Fine Arts and Creative Writing at the New Mexico State University and an MFA in Emergent Digital Practices from the University of Denver. She is an interdisciplinary artist with a focus on digital media.

She has been an advocate for victims of sexual abuse and for people with disabilities. She fights against mental health stigma, and is an active member in the Queer community. Her practice includes creating digital landscapes, 3D modeling, Animation, Sound Design, Wearable Technology, Creative Coding, and Photography. She is knowledgeable in programs such as Maya, Blender, Photoshop, InDesign, After Effects, Affinity Photo, Affinity Design, Unity, Unreal, Final Cut Pro, Divinci Resolve, Max MSP, Arduino, Processing, Spark AR, Substance Painter.

She is currently an artist in residence at Redline Contemporary Art Center where she mentors students in the (E)ducation (P)artnership (I)nitiative for the (C)reative, aka EPIC Arts Program. She has shown her work in Ars Electronica Galley Spaces (Online), CADAF Contemporary & Digital Art Fair (Online), Social Distance Gallery (Online), RedLine Juried Exhibition at RedLine Contemporary Art Center (Denver, CO), Proud+, The Studio Door (San Fransico, CA), Coalesce && Object at the Vicky Myhren Gallery (Denver. CO), and OUTSIDERS at Leon Gallery (Denver, CO).