Mike Keaveney [Interview]

"Photographs exist as a fusion of icon and index. Like a fire producing smoke they show evidence, and like a statue they resemble. Combination of icon and index, paired with a reduction of the human through technological mediation make the photograph a powerful tool for representation. They assume the role of truth teller through the processes of their own creation, representing events and replacing memory. Despite these qualities, photographs like all other forms of depiction are deceptions. They signify but are not the signifier, they reduce the human but are constructed and manipulated, and with technological advances they have largely become incomprehensible, existing in a vast sea of creation and distribution.

“An Icon has a physical resemblance to the signified, the thing being represented.

An Index shows evidence of what’s being represented.”

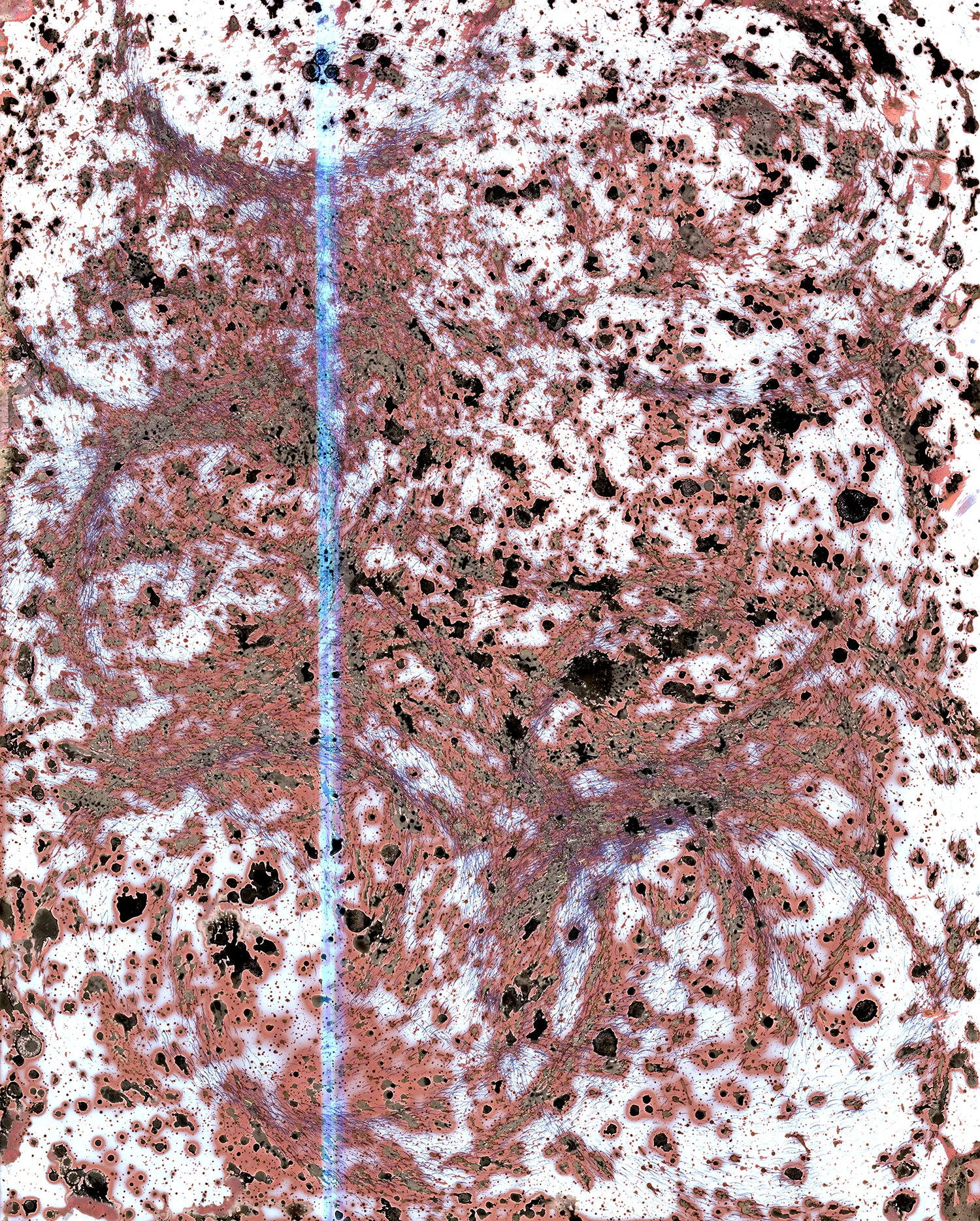

My artistic practice exists within these conflicting photographic characteristics. I manipulate photographic materials, find alternative uses for obsolete recording machines, and reinsert the human hand into the photograph through physical and chemical processes. These manipulations result in varying degrees of abstraction that move the image away from representation, transforming the real and known into ambiguous image-objects.

“So much is happening between here and there, so difficult has it become to get a grip on the procedures that lead from here to there, that we are forced to confront the possibility that there was never a ‘here’ or ‘there’ to begin with; both are a product of the between.” (Geoffrey Winthrop-Young, The Kulter of Cultural Techniques)

Layers of construction, deconstruction, technology, and process abstract the origins of materials, making it difficult to perceive anything as known. I attempt to peel back these layers within photography, to go beyond the screen and surface of the image, to foreground hidden properties and to reconstruct the known. "

-Mike Keaveney

Interview with Mike Keaveney

Digital Resident, June 2018

MHM: What is your background in art and what brought you to make the work you do today?

MK: My work varies, but the majority of my practice has been based within photography. This started when I was a kid, incessantly photographing and archiving 4x6 photographs in my desk drawers. Then when digital cameras became more prevalent I no longer saw the value in tangible images and threw them away. Later my parents Dell desktop crashed and I no longer had the analog or digital.

Other influences include but are not limited to:

McDonald's, skateboarding, abandoned steel/coal mills, order picking, chemical reactions, screen printing, home staging, the city of Philadelphia, plants, concrete, beer, the viaduct, the high-line before it got developed, dancing, folk punk, Catholicism, the suburbs of Reading, Pa, Amity skate park, undergrad, learning about art/history, archaeological, Andres Serrano’s urine soaked photo of Jesus, parking lots, cheap beer, sunlight, public gardens, education, evolution, every person I’ve been lucky enough to call a friend, family, collaborative spaces, the blues, drag performers, live music, mountains, the scrap exchange, Billie Holiday, weed, digital technology, satellites, under-sea fiber optic cables, artists, the history of photography, musicians, mythology, friends pissing on trump flags, social workers, public organizers, film, experimental art, teaching kids to create with reuse materials, buskers, John Baldessari burning all his work, trees, and sunsets at construction sites.

“ Unlike other cameras that require reflected sunlight, scanners produce their own light, making every image they produce a self-portrait.”

MHM: What attracts you to the scanner as a photographic tool? Physically, poetically, or in context of the lineage of photography?

MK: Scanners interest me for a variety of reasons. One being their semi-obsolete nature, either through technological advances or planned obsolescence these high powered/slow cameras easily become outdated. Currently making them one of the most accessible and affordable cameras available. Their devaluation frees me to approach them as a digital blank recording surface, like a piece of paper or canvas. The difference being that the scanner pulls information and form through the objective world.

In relationship with the lineage of photography, the kind of images produced by the scanner reference photography’s earliest images. The result of placing a flower on the scanner produces form and negative space, not unlike the early botanical contact prints of William Henry Fox Talbot and Anna Atkins.

The way that the scanner records images is another area of interest for me. Flatbed scanners produce white light during the process of recording. This light hits whatever is on the platen, bounces back down, and is recorded. Unlike other cameras that require reflected sunlight, scanners produce their own light, making every image they produce a self-portrait. This production of white light is also why the images taken with the burning scanner turned out pink.

MHM: Looking at your scanner setup in the mall, the scanner on fire, and some of your other site specific installations makes one wonder: is performance an important aspect of your work?

MK: Performance is an area that I have recently been grappling with and trying to find my place within. I believe that most things are performances including everyday interactions, and undoubtable within the visual arts. That being said everyone has a choice about how much they want to project or conceal their own actions, and both are powerful tools. Within my own work I find process, materials, and traces of actions important. I use them to representing a body or idea, that isn’t specifically my own.

“Photography itself exists within the grey areas of natural and artificial, it is reliant on objects, the exterior world, and reflections of light. It is reliant on the natural, and produces something constructed or artificial”

MHM: Though your projects are tied together in overt ways, they also seem insular. What is your process for engaging in and completing a project?

MK: Sometimes it ends after a specific action like scanning plants in a mall. However, finishing one action doesn’t mean it’s complete, and I see my work as a constant building with variation in actions or processes but without completion. Older projects will be built upon, and their imagery will be re-purposed.

MHM: Your work plays in the grey area between the natural and artificial. How do you feel your research on the relationship between “Icon” and “Index” influences your understanding of that space?

MK: Photography itself exists within the grey areas of natural and artificial, it is reliant on objects, the exterior world, and reflections of light. It is reliant on the natural, and produces something constructed or artificial.

MHM: Do you think that as a whole, our relationship to photography has altered the way that memory and perception function?

MK: Definitely, since photography was invented it has been used as a stand in for places that we’ve never been and experiences we’ve never had. With the creation of the internet, images have undoubtedly reached a new level of proliferation and integration into our daily lives and cognition.

MHM: Do you want your work to convey criticism?

MK: Criticism is present, at the same time my work falls in an in-between of criticism and compliance. I do a lot of work within commercial construction, development sites, abandoned sites, and malls, all of which offer the very direct narrative of right and wrong (nature vs. development, Applebee’s vs. Yellowstone), which I know is not the case. All of these changes to the environment and the decisions about the way that we live are multilayered and convoluted through process, class, and labor. I want my work to convey criticism, conflict, and to address the feelings of futility that these systems produce.

Example: I recently did an exercise that included photographing and making rubbings with silver gelatin paper in commercial parking lots, intended as an re-envisioning of landscape photography in a modern context. During the process I found myself eating in a McDonalds parking lot, on top of that I worked as a fry cook at McDonald’s for five years.

“[Loss is] necessary for the creation of something new. It’s a pre-requisite for change.”

MHM: What influential text or other media have you been exposed to? Perhaps something pivotal and current.

MK: I was just exposed to Cyprien Gaillard’s work last night and I’ve been watching and reading about it for most of the day. His work involves entropic views of architecture and landscape within a modern context, like in his instillation The Recovery of Discovery where he made a pyramid of beer cases within a gallery that viewers come to, drink, smoke, and socialize as the pyramid collapsed in on itself through the act of consumption. His work references Robert Smithson works and writings, as well as Gordon Matta-Clark who are both influential in my practice.

Link: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6qmrHCC6ZoM

MHM: As someone who works with themes of development and loss, what is your attachment to the place you are currently in? Do you feel that a sense of home is important in your work?

MK: Before moving to Chapel Hill, NC to pursue my MFA I was living in Philadelphia, which is where the majority of my friends and family are located. I had a strong sense of home and a connection to the cities architecture through work and skateboarding, which drove a lot of my site specific work. This was especially true for the viaduct, an abandoned rail line that runs above parts of the city. It’s concrete was deteriorating and it had become overgrown with vegetation, including wildflowers, large trees, and fields. NC has begun to also feel like home, it’s just situated within a different landscapes systems of alteration.

MHM: What do you find beautiful about loss?

MK: It’s going to sound cliché but it’s necessary for the creation of something new. It’s a pre-requisite for change.

MHM: What project could you envision taking on if time and funds were no impediment?

MK: I would install a giant skylight that is constructed with layered optic lenses. During the right conditions it would concentrate the sunlight into a singular point, burning and marking the floor. Similar to burning a leaf with a magnified glass only the leaf or floor would be made of flatbed scanners that are autonomously recording and archiving the viewers movements, and being broken and burned by the concentrated sunlight.