Interview with Adam Crowley

Interview With Adam Crowley

November 2022 Digital Resident

A conversation with Clay and Olivia of Mineral House Media

MHM: In your residency, you spoke about the question of why to paint. Can you touch on that here? Do you consider yourself a “painter” over the more broad title of “artist,” or is there even an important distinction between these titles?

AC: This is a very interesting question, it’s been in my head for days now! I do consider myself a painter foremost. I’m honestly not sure I can give myself the title of artist, or maybe at least I can’t bestow the word ART on everything that comes out of my studio. Some people can make 3,000 paintings, and it could be argued that none of them were art (Thomas Kinkaide, Norman Rockwell, KAWS are a few names whose arguments I’ve heard) and others can make relatively few and be bestowed that grand title of artist. But I’m also not sure when a thing becomes art. Can something achieve “art”, and then lose it again? Maybe I’m thinking about this too mystically… Maybe the entirety of one's output is art? Is a painting by Caravaggio the same Art as a grid by Hanne Darboven? I don’t know. I’m stumped. I think it’s going to take me a long time to figure this question out.

This question is surely one of the reasons painting should continue. Another is the fluidity of the practice itself. It can’t really be nailed down. After the camera was invented, painting shifted into unmapped territories. After the “Painting is Dead” arguments were made, a new crop of painters rose up in defiance. I can list a dedicated and interesting painter for every genre that has been called stale or obsolete. Technology hasn’t killed off painting yet, and honestly in some ways it has made it stronger. For every bombastic multi sensorial art room filled with a million LEDs and sensors to pick up ambient temperature fluctuations and olfactory bladders suspended from the ceiling that mist the unsuspecting crowd with the smell of lilacs, all to the soundtrack of some obscure video game, there will be a painting in gallery made that much more important. Both are acceptable, maybe even necessary. It’s a balance.

MHM: How do you choose which photographs to paint from? Do you tend to work piece-by-piece, or do you like to plan groupings of work?

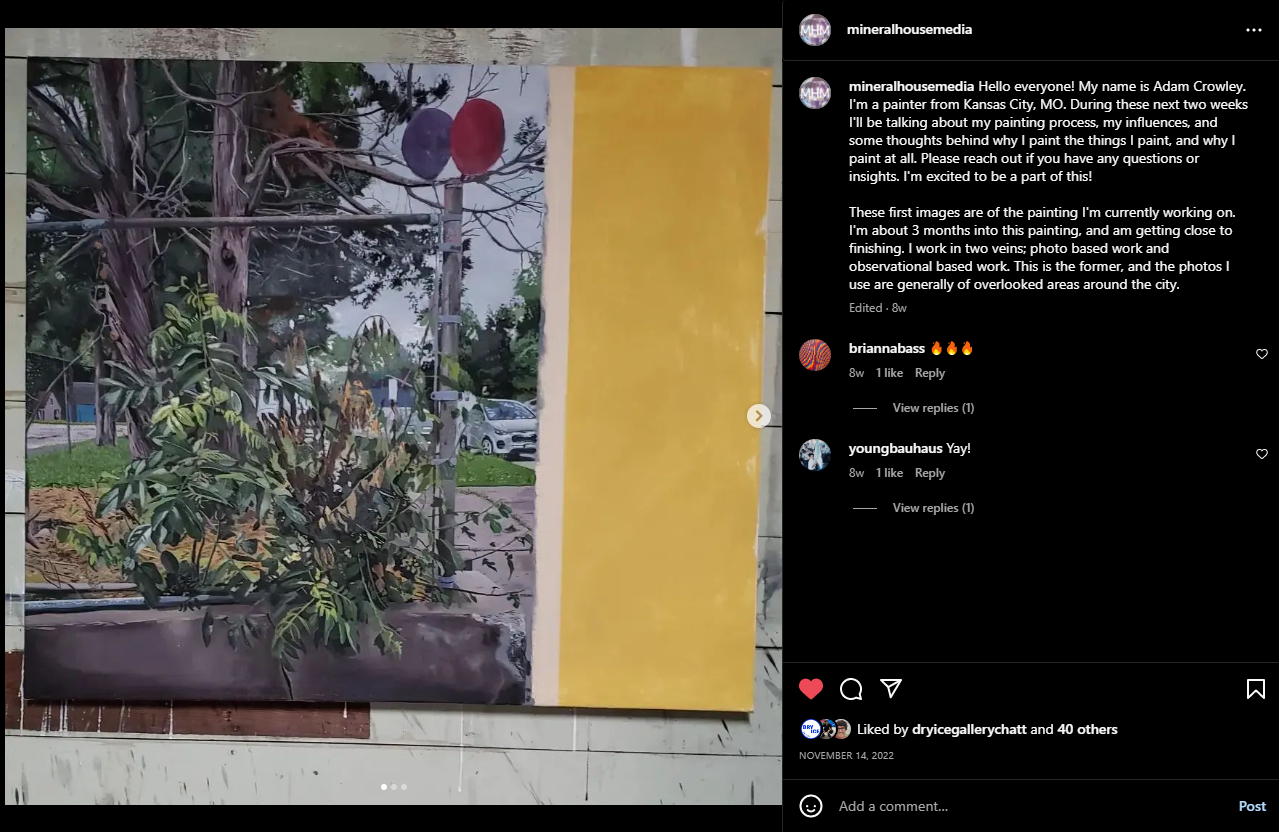

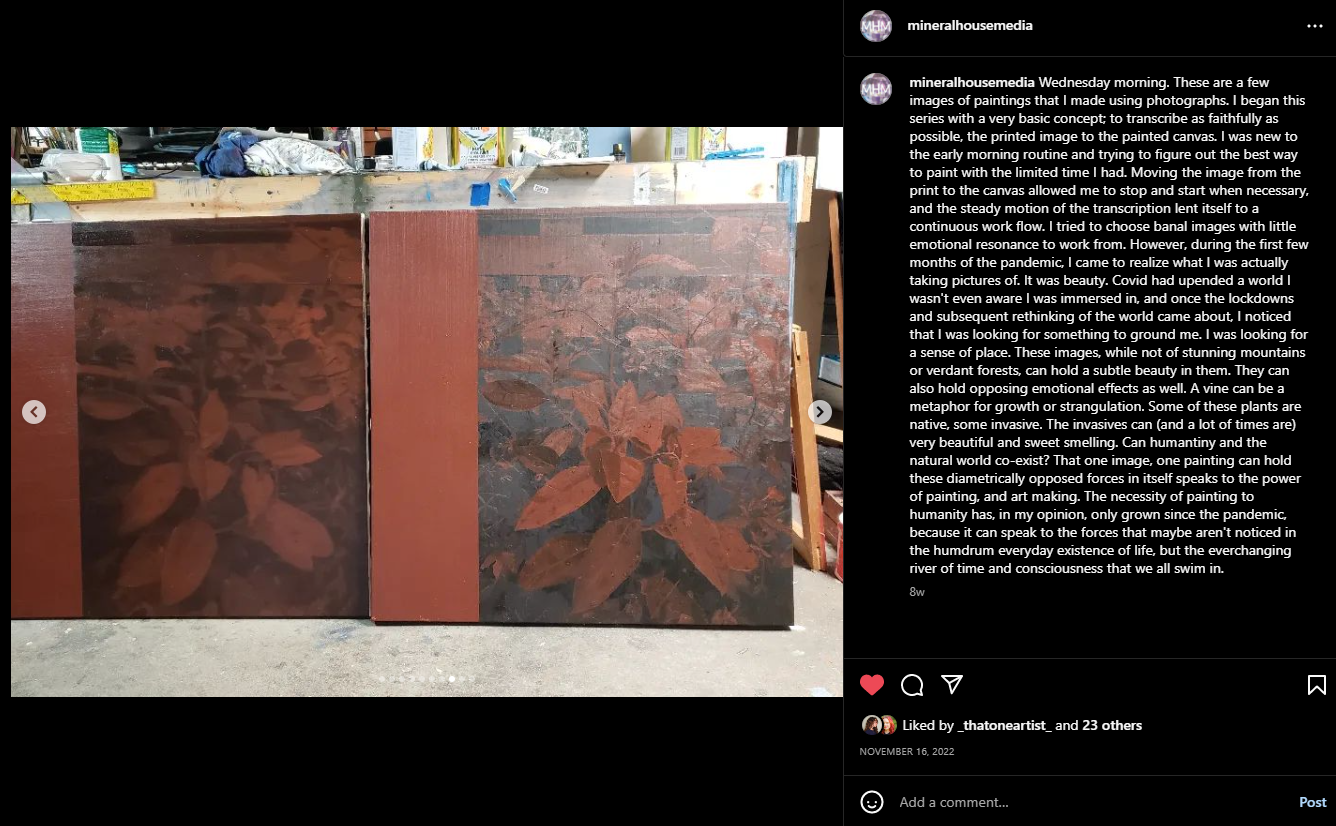

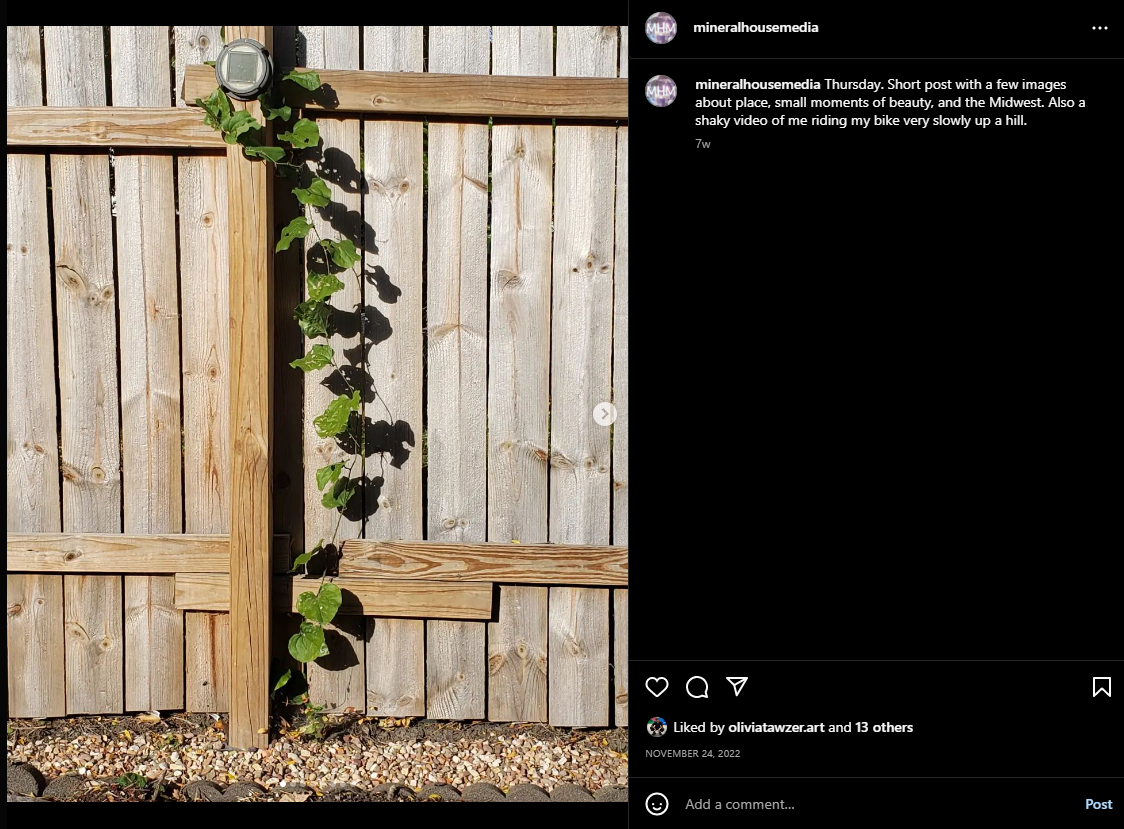

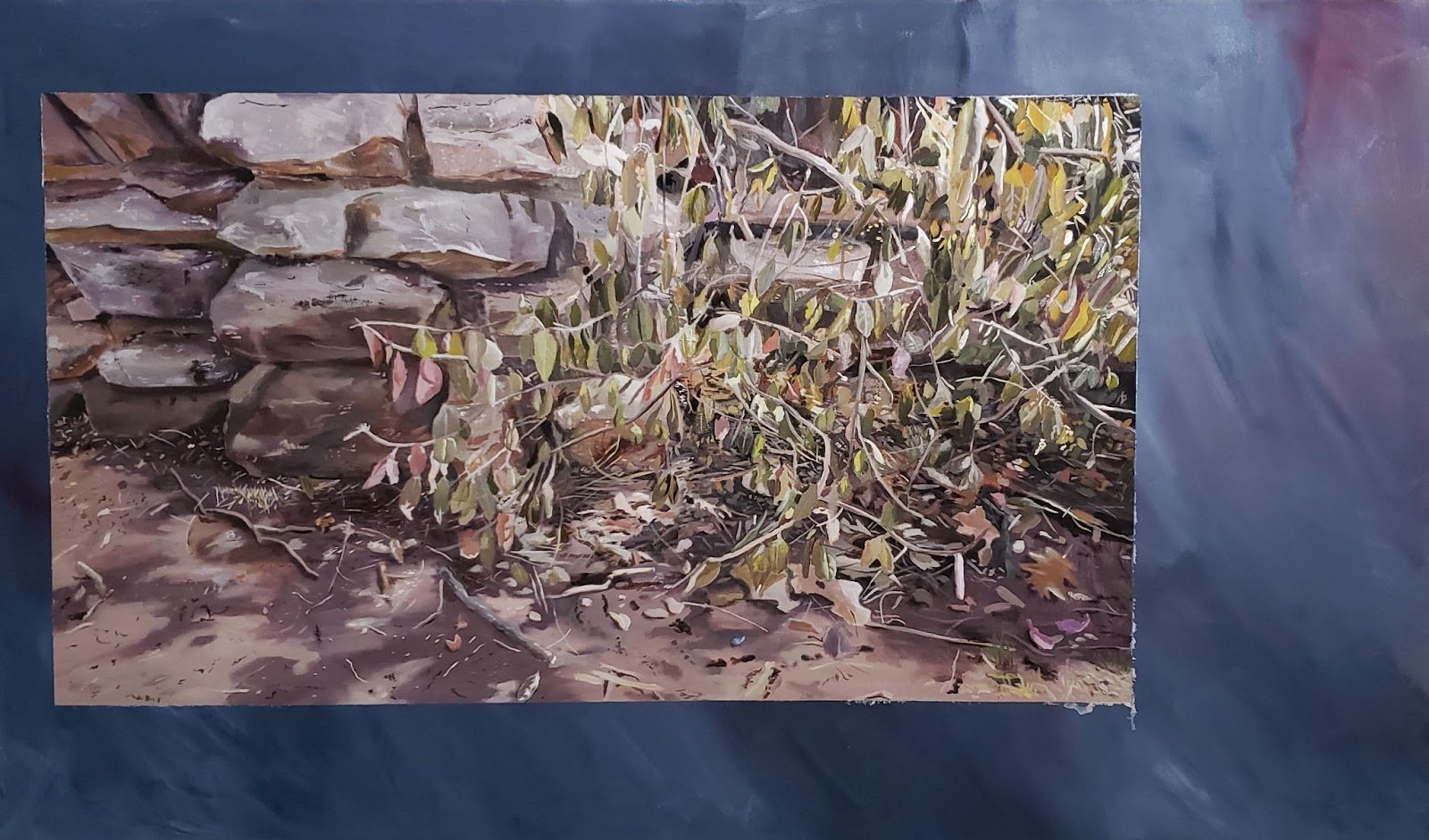

AC: There are several considerations I try to think about when deciding on a photograph. First are formal considerations; color, composition. I think my photo based paintings are really more traditional in that sense than the still life paintings. It’s made me very aware of how difficult it is to take a compositionally sound picture! I also like to have a meeting of the natural world and the man made. I like weedy, busy fence lines or trees growing out of parking lots. For a long time I’ve wanted to do a series of the trees that grow alongside the highway on ramps or medians, but I haven't been able to get decent photos yet. I consciously try to not make any of these paintings pro natural world or pro civilization. I want them to be a moment, dually unique and completely commonplace. To hopefully show the history and the future of a particular spot in the world.

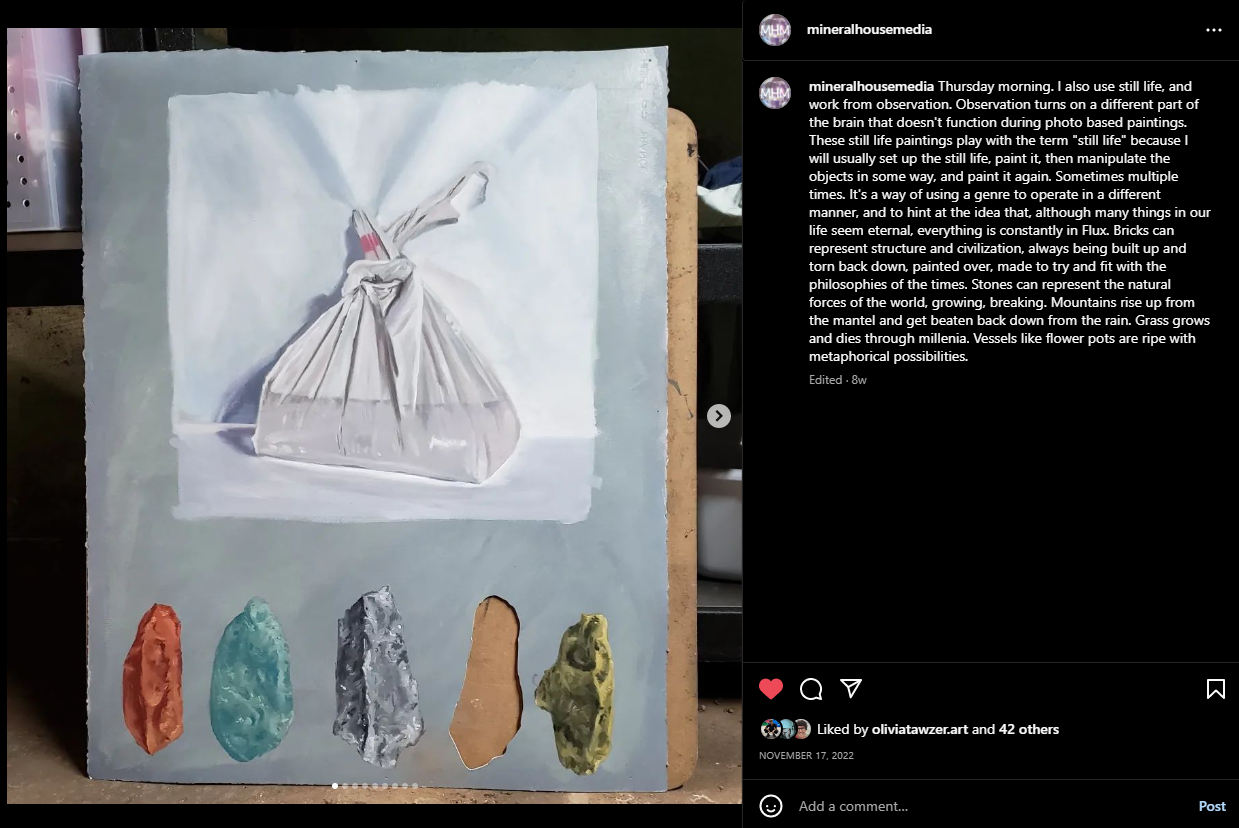

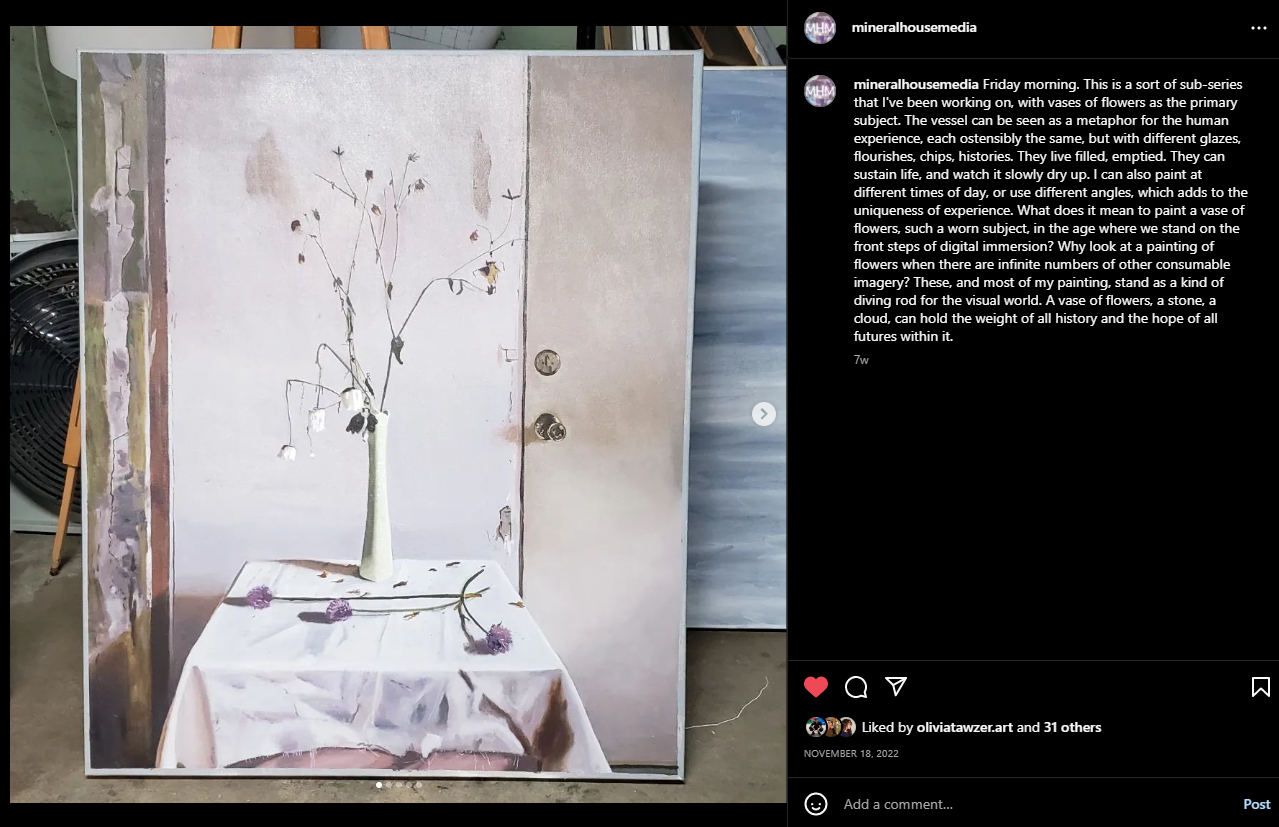

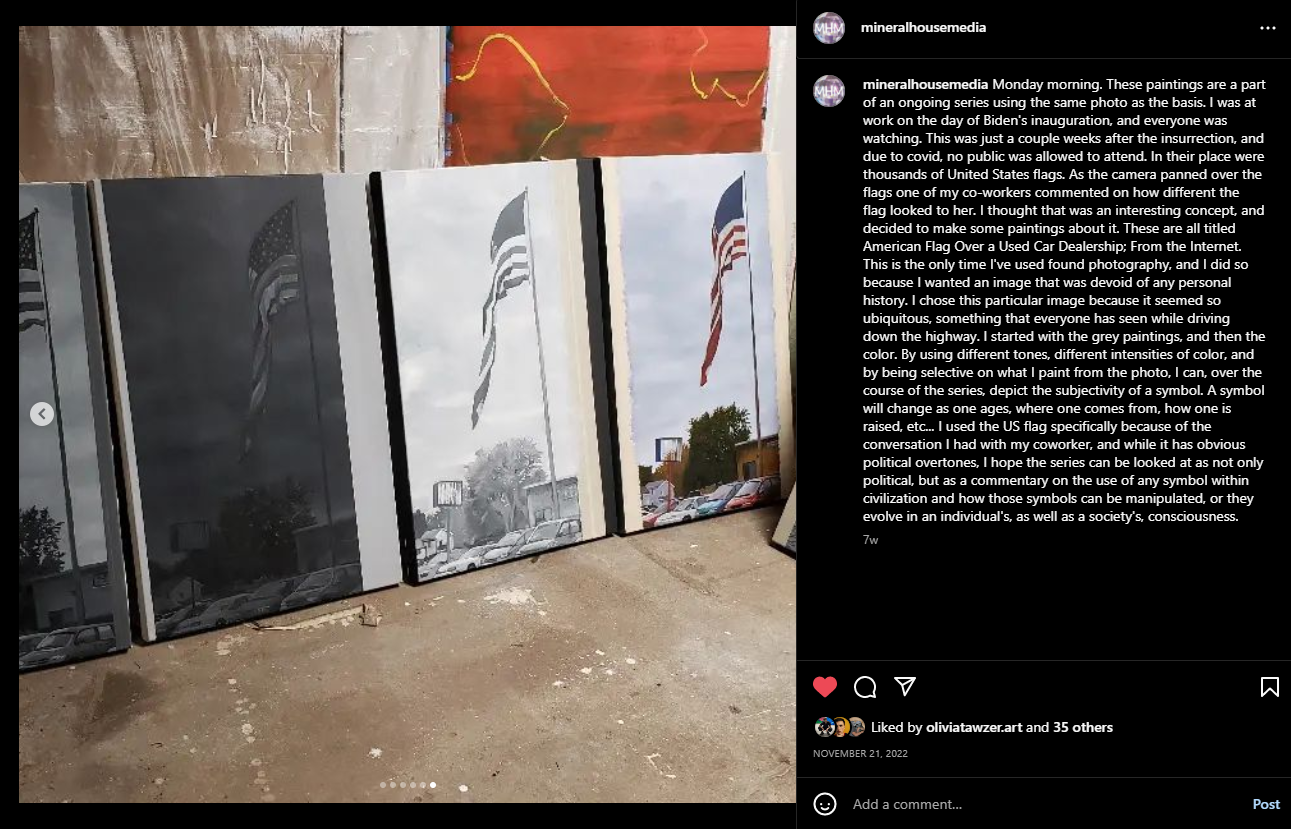

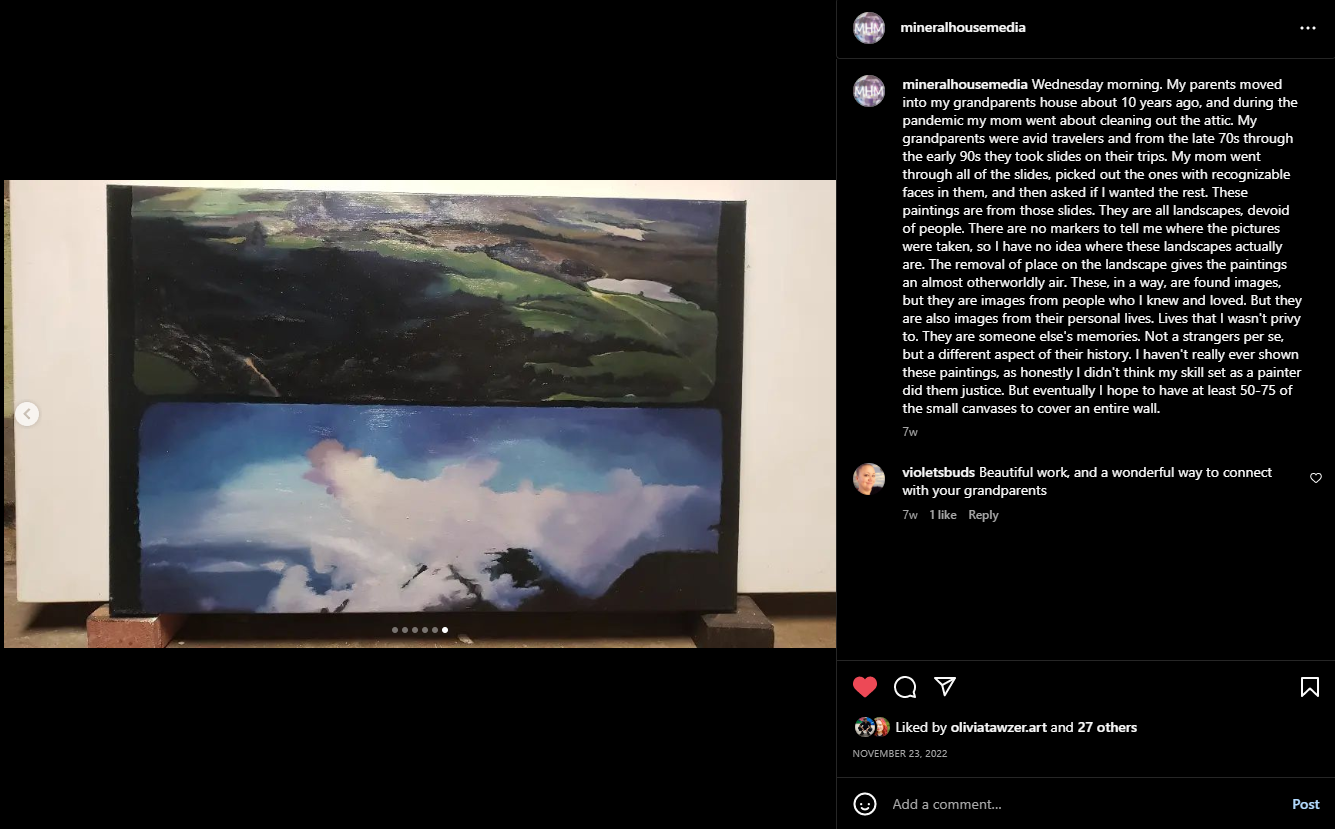

I work in what you might call themes. I think the photo based paintings are one theme, since they all work in a similar format, with the image being surrounded by the abstract mark making, they generally use what I’ve mentioned above; nature, civilization, formal painting decisions, etc.. The still life paintings are a second theme, in that they all work in a similar thread; several images of the still life on a single canvas, with the object manipulated in some way. There are three series that I am working on that I have the entire series in mind when I’m painting. An American Flag Above a Used Car Dealership; From the Internet is a series I’m working on using a single image, in different color schemes. Another is a series of landscapes I’m painting from a bunch of old slides that were found in my grandparents house. The ideas that were the catalyst for these two series will (hopefully) become more concrete as the series grows. Currently I want to make at least 50 paintings from the slides, and probably around 30 of the flag.

MHM: What is the difference in your experience painting from live versus photographs?

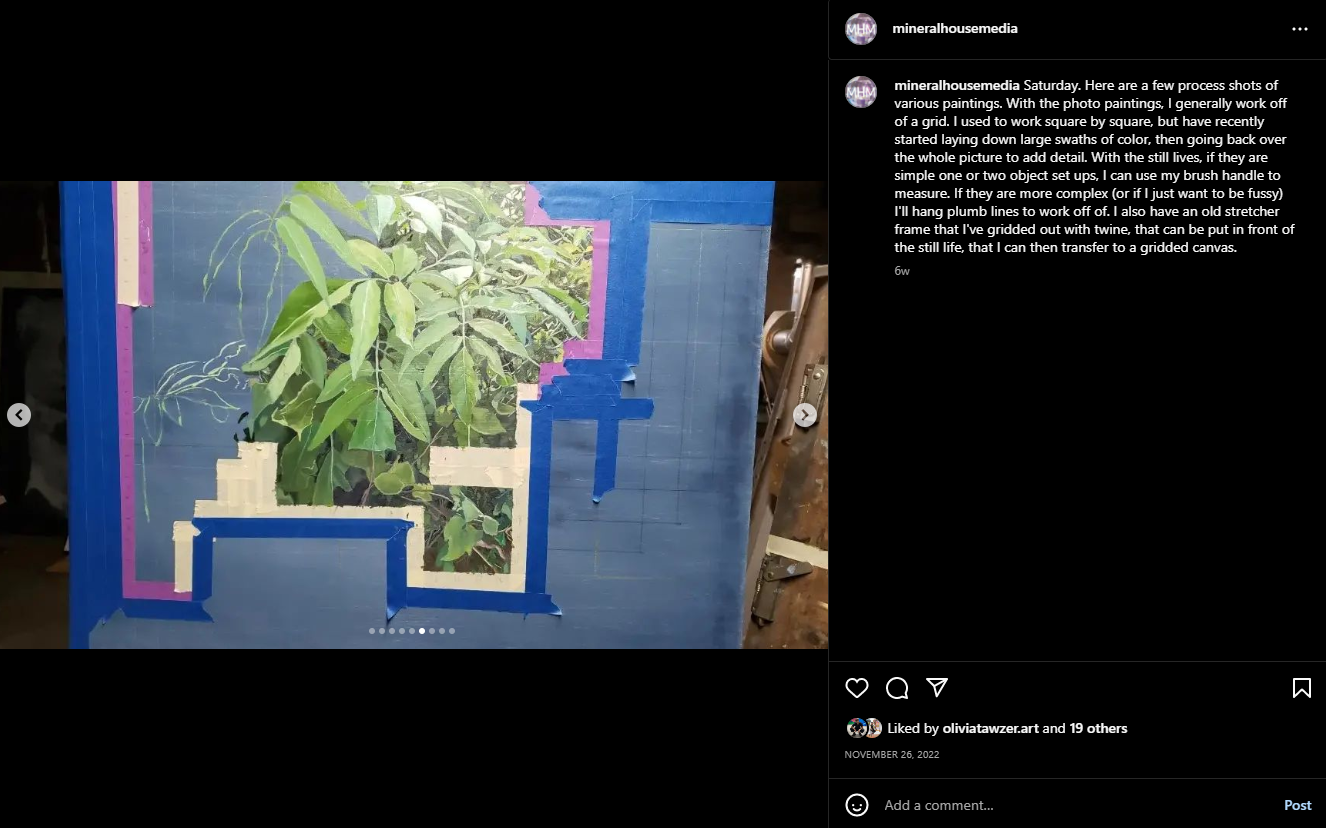

AC: It's a different process. The photo paintings are more like transcription, slowly moving the image from one surface to another. I feel like there are more choices working from observation, the build up of the painting is different. There’s sort of a looseness in observation that I’m always wrestling with. All of my paintings are pretty structured, and I have a dedicated system that I use to work on the canvases. I’m not really someone who can just sit down in front of a blank surface and start working. I need a structure and a process to work toward the realized piece. That's easier with the photo paintings, and I’m always trying to find a grid in which to house the still life stuff.

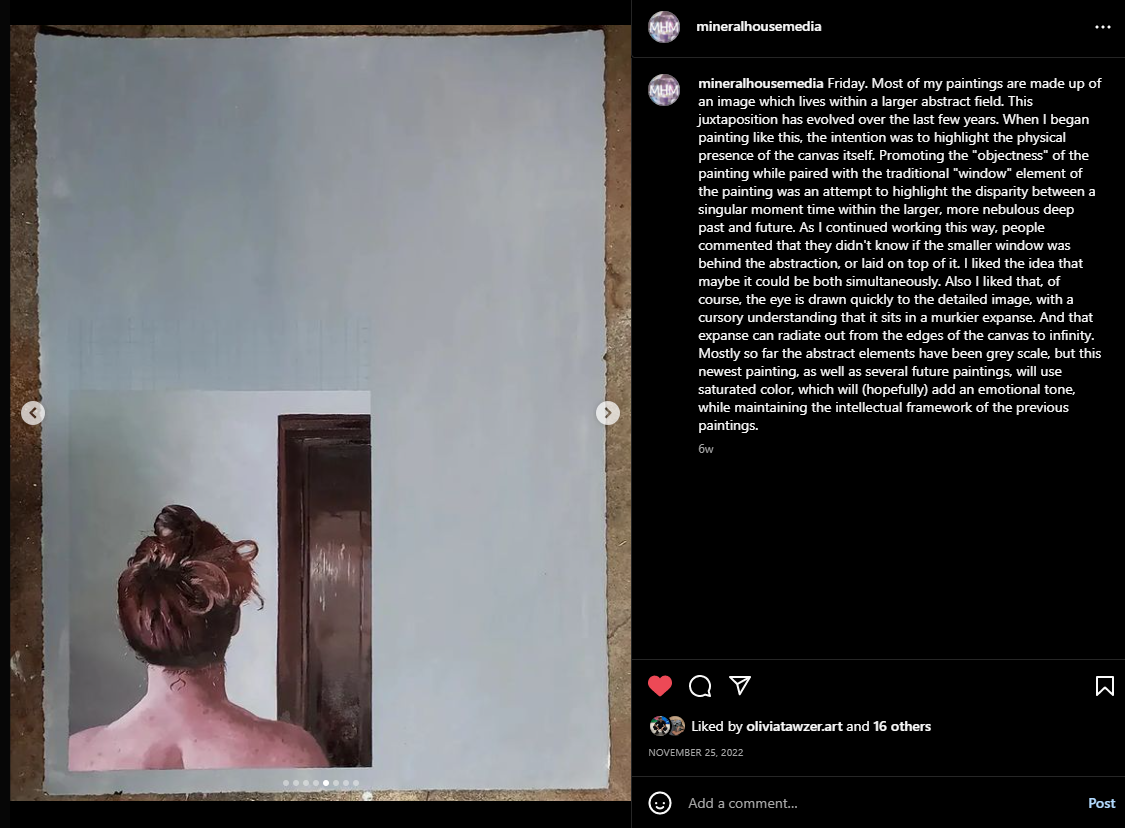

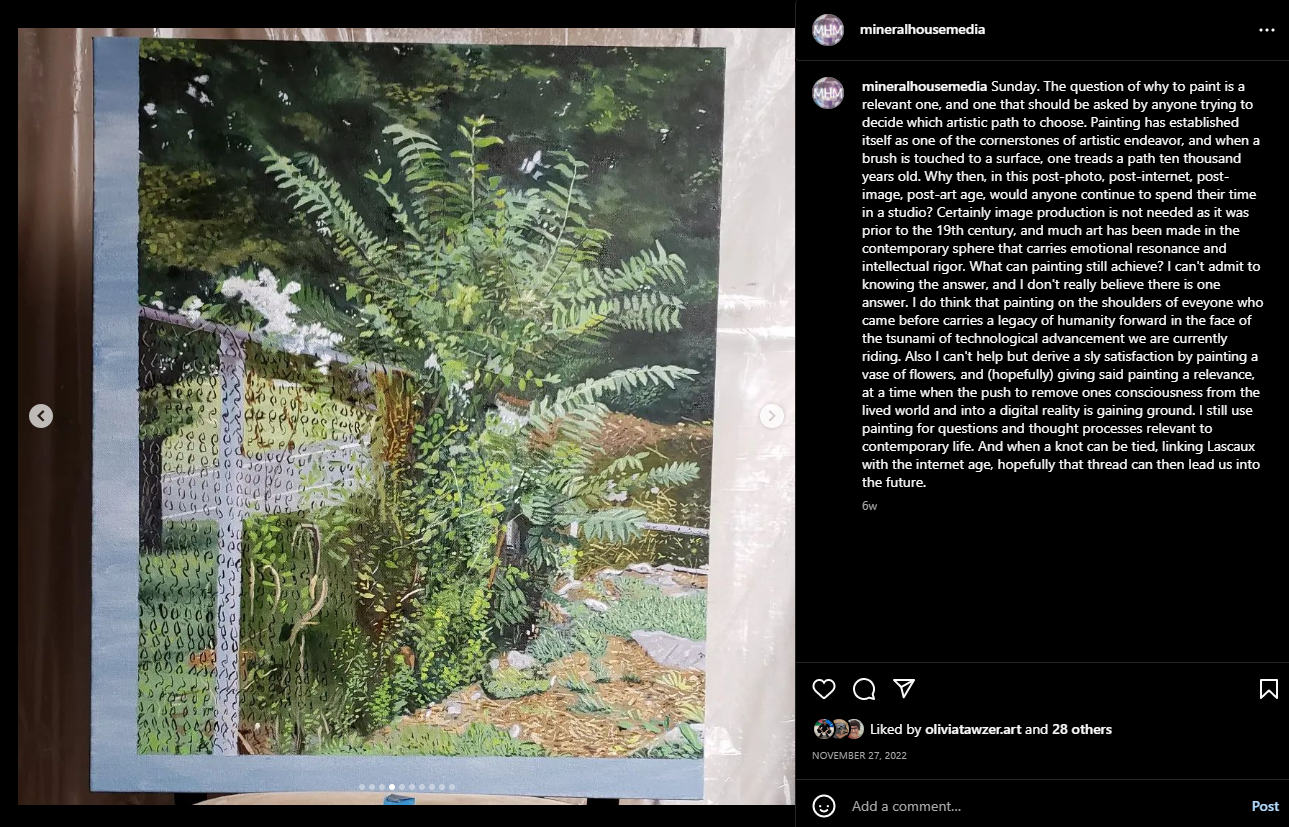

MHM: Many of your paintings consist of a representational image paired with an abstract element, either as a background or a type of border. Will you speak to your thoughts behind your decision to pair images in this way?

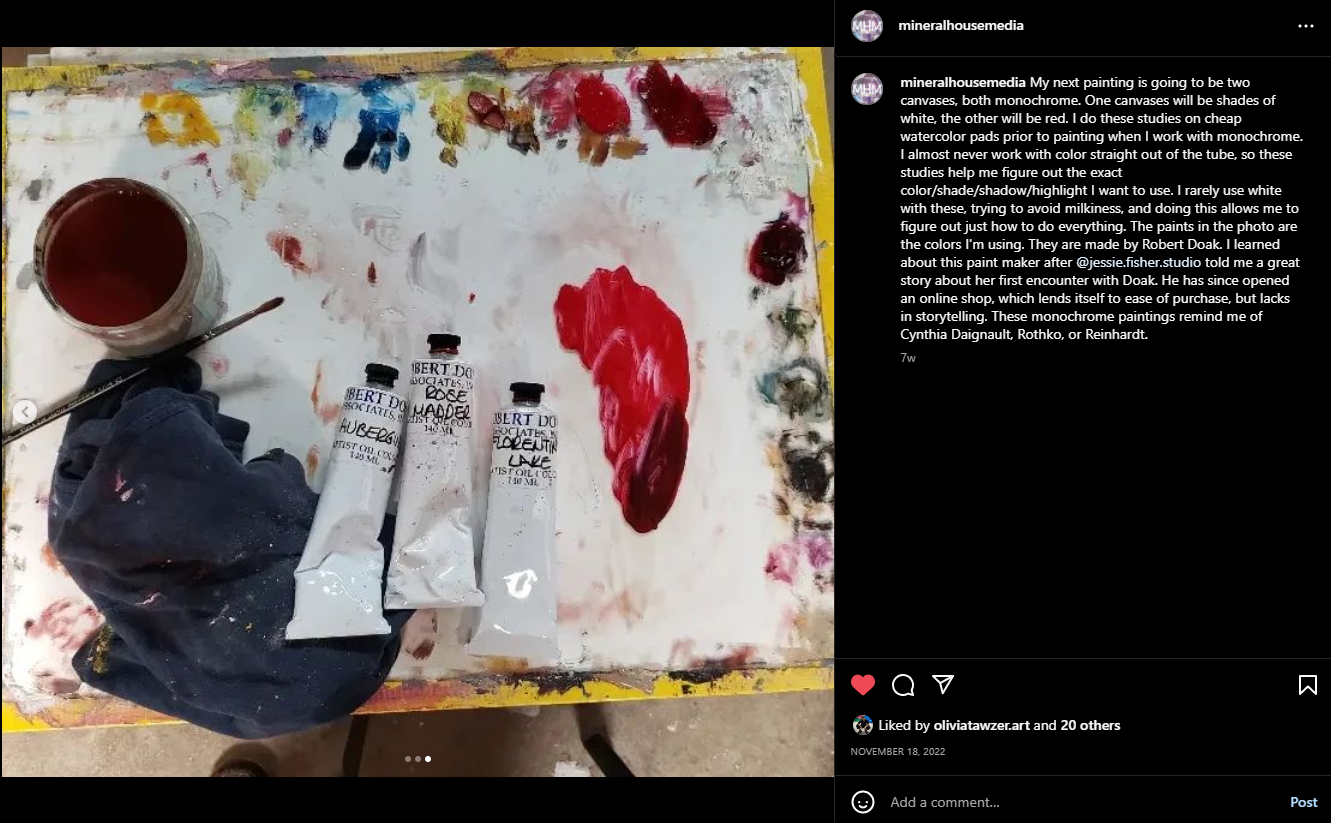

AC: It began as way to promote the objectness of the painting itself, sort of a juxtaposition of the abstract interest in surface and the traditional idea of the painting as a window. As I kept working with this idea, I realized that it also promoted the momentary quality of the image. It gave the painting an absolute focal point that the eye is drawn to first, and then moves back from. I like the concept of one moment, suspended in time, encapsulated by a larger, less definable girding. Girding meaning structure which the painting is set upon, but also structure as elements in the world that allow for a precise moment in time to occur. The “square within a square” set up I’ve been using the past few years has been really helpful for me in terms of finding a solid footing in which to push off from in terms of building a cohesive series of work. I had an exhibition in August at the Kansas City Artist Coalition, and after the show was up, I felt like maybe this would be a good time to start thinking about a new direction. Most of the paintings I’ve worked on like this have a gray or muted blue abstract element, and I am currently working on some different color choices for those spaces. It’s interesting, because this new direction is bringing up some new questions; what color should I choose, what do more saturated colors mean in this regard, am I trying to elicit a more emotive response with color, or can red or yellow or green serve in the same way as gray? I haven't landed on a concrete answer yet, but it's interesting to think about. Usually I’ve found that these questions work themselves out as the paintings pile up.

MHM: Do you listen to anything while you paint? What does your time in the studio look like?

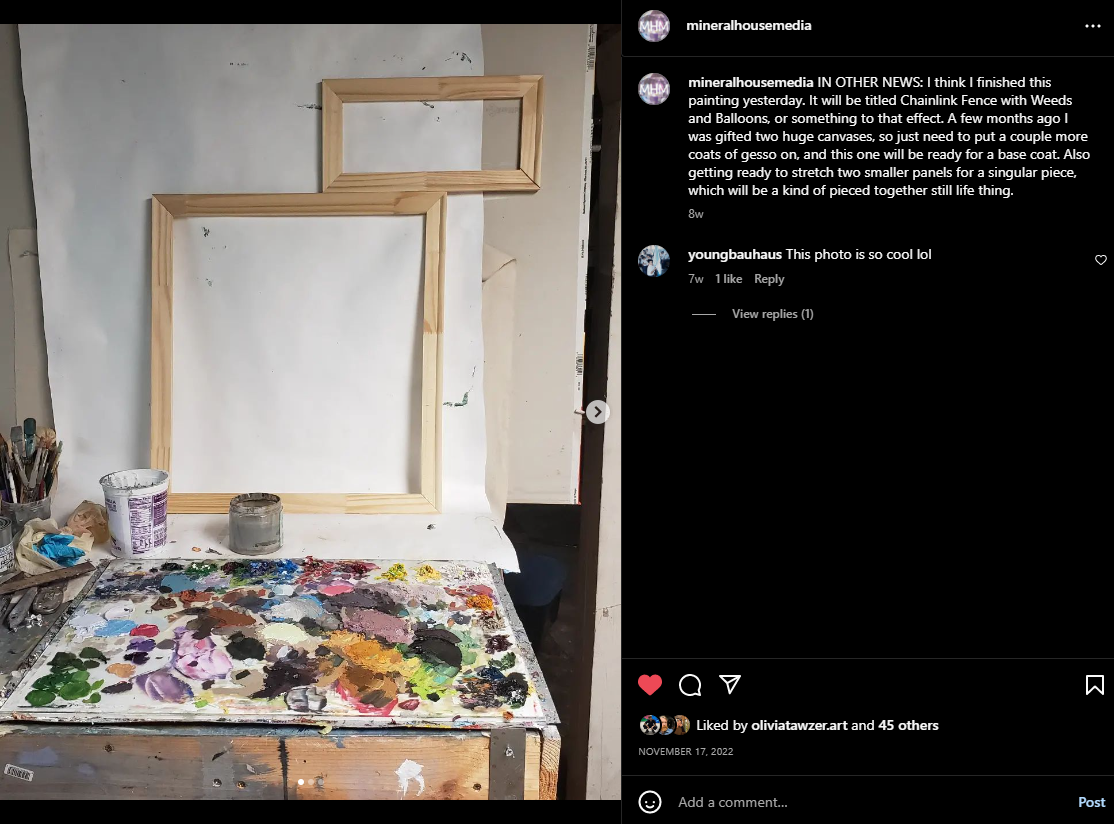

AC: My studio time starts very early, usually around 5 am, and I work until around 6:45 or 7 on the weekdays, and basically until my wife and daughter wake up on the weekends. I take Sundays off. Since it is a rather compressed schedule I try to always have something ready for me when I finish a painting. Once I have the photograph I’m working on gridded out, or the still life set up, it’s basically setting my coffee down and start mixing color. This type of schedule doesn't allow for much down time. I basically feel like I need to work as much as possible given the time restraint. Since I start working so early, and there are other people still asleep in the house, I don't usually listen to anything, and I have found that I enjoy that. It’s a quiet time in the usually loud world. If I have a cleaning/canvas stretching/palette scraping day I usually put some type of music on: Preoccupations, Sarah Davachi, Thom Yorke, The Body, Ryuichi Sakamoto, Debussy, Gangstarr, whatever sounds good at the time.

MHM: When and why did you start paying attention to overlooked urban spaces as subject matter?

AC: Probably six or seven years ago I started working on painting from photos, early in that experiment was when I decided on painting clouds. I liked that clouds can be completely unique and absolutely banal at the same time. And that almost everyone who has ever lived has seen a cloud. They are ubiquitous in the world. From there I started looking for other instances of that idea, and I started to find them in disused spaces. This weed could be a beautiful fragrant invasive plant that is slowly consuming every fallow lot for miles, or it could be a humble native plant, and the sole source of food for a particular caterpillar. They seem to have a transitional feel about them, a vein in the great kneading of civilization and the world. This was all very cool, rational painting until the pandemic. After 2020, when the vein of civilization and the world wrenched, and we were home-bound, I began to realize that one thing I was searching for in these places was beauty and the idea that something could still be beautiful, in spite of everything going on. Really that beauty was beyond everything that was going on in human society. And you don't have to find some majestic mountain outcropping or cerulean island paradise to experience moments of stunning beauty. The sunlight through a leaf, or the shadow of a retaining wall, or the warm color of a rusted chain link fence against the green of a forgotten city easement can spark moments of real beauty. It’s a less rational way of painting, and I definitely have to walk the line of sentimentality, but honestly I think it’s an important topic, and one that is vastly undervalued. Beauty is one of the great joys of living, and is probably in some fashion a part of every wonderful memory people keep with them. And it’s absolutely everywhere. It’s a sustainable resource! But unlike wind or geothermal energy, it wont power your house, but it can give meaning to your existence. It’s surely the reason people continue to make things, and it’s most likely the base element in that all too elusive crystalline structure called art.

MHM: How has having a regular studio routine changed your practice? Do you work on the same painting each day until it’s done?

AC: My studio routine has significantly improved my work. I fought the idea of routine as a younger person, as I had a sort of silly romantic notion that routine was uncreative. As i got older, however, I found that the routine actually gave me the opportunity to grow and improve both the technical aspect of painting as well as the conceptual or philosophical goals I wanted to work with. A routine helps me focus my energy, and that energy continues with me through the rest of the day. I usually try to have a couple paintings “in the wings”, because there will be times when the painting I’m working on is too wet or something, but that's usually at the beginning. When I’m really down in the painting, it’s pretty much one at a time.

MHM: You mentioned books have a heavy influence on your practice. Was there ever a moment when a book pivotally changed your work, or drastically shifted the context for it?

AC: Jerusalem by Alan Moore gave me a completely new perspective on how time can be interpreted. The book centers on one town in England, and the premise is the entire history and future of this particular place in the world is being played out simultaneously. It’s a wild book. There are also several authors, Kazuo Ishiguro, Yoko Ogawa, that write with a restraint that sort of permeates the book. They aren't emotionless by any means, but it isn't heart on your sleeve stuff by any means. I appreciate that. All of the books that I’ve read by them have a cool blue feeling to me. Never Let Me Go by Ishiguro and both books I’ve read by Ogawa, The Memory Police and The Housekeeper and the Professor have that. It’s a wonderful mood, not overly dramatic or saccharine, and I hope my paintings can give the same effect.

As far as art books, Richter’s Daily Practice of Painting is great, and one I return to time after time. Just Painting is a collection of writings about Peter Dreher, compiled, I believe, by Hans Ulrich Obrist. It is also a really great, slim text that I can pick up any time and rekindle some thoughts on painting and art. The last one I’ll mention is the Vija Celmins monograph published by Phaidon. It has an interview with Celmins given by Robert Gober, and I love the dual artist conversation that happens.

MHM: Who is your favorite artist, and why?

AC: I have a hard time singling one artist out, but I can give a few examples of artists that have been influential to me. Gerhard Richter was an early influence. I have a vested interest in painting, and what place painting has in contemporary culture, and Richter has spent years tackling this question. The fluidity from imagery to abstraction, minimalism, sculpture, and installation that his oeuvre contains is really impressive, and the almost scientific testing he has put painting through has been a big inspiration to me. Vija Celmins’ images of the ocean, desert floor, moon surface, etc… achieved a sense of eternity through a highly constrained and rigorous workmanship. Peter Dreher painted the same water glass over 5,000 times, picking up minute differences in light and reflection to give each painting an absolute uniqueness. I guess I feel inspired by artists with a sense of commitment, a sense of determination, a sense of devotion. Also if any artist has published writings,I’m generally interested. Ad Reinhardt, Agnes Martin, Chardin, Ellen Altfest, Catherine Murphy, Richard Estes, Robert Bechtle, Antonio Lopez-Garcia, Luca Bertolo, James White, and Andrew Grassie are a few names that have been useful to my development as a painter.

MHM: Do you collect more photographs than you paint? What happens to the extras?

AC: Absolutely. The phone camera has allowed basically an unlimited amount of possible reference photos to be taken, so I try to take pictures of anything that remotely catches my attention. From there I’ll go back through my photo gallery, delete the ones that dont hold up, and transfer the rest to my computer. Then another round of cutting will occur when I transfer that group to an “image” folder I have on my desktop. From there I’ll pick out whatever I want to work on, and either print that image from my printer, or send it to a photo lab if I want a better quality. Once I have all the physical copies, I will edit yet again if the colors don't work or the composition looks different on paper. It’s an involved process, but the images that do make the cut are definitely the cream of the crop.

MHM: How does your family, immediate and extended, affect your thinking and practice?

AC: Having a kid completely changed the way I view the world, and the way I go through it. It changed my whole life, the routine, how I speed my free time, when I paint. It absolutely made me slow down and look at the landscape through different eyes. I think about my parents, grandparents, great-grandparents, and the generations that came before quite a bit too. Not simply through painting, but just as I go through my life. The idea that I’m one link in a chain that stretches infinitely backwards and forwards hopefully comes through in my work.

MHM: You talked briefly during your residency on why you paint. Could you dive deeper into your reasons here?

AC: At it’s most basic, I would say that I’ve never lost interest! That might not be a terribly inspired answer, but I have always loved to make pictures. Since I was very young, I have been interested and have found that I could express things in my head that I couldn't put into words. As I grew up and found more artists, writers, philosophers, etc… I became interested in the ways meaning could be injected into a painting, and was thrilled in trying to decipher the hidden languages in art. And that interest has never waned! I feel like I’m just as excited about painting as I was when I was 15 and just discovering Dali or the German Expressionists. I’ll turn 42 in January and I can honestly say that I haven’t been this excited about my work and the work around me in years, and maybe ever. I will also say that it has become something I need to do. If I miss 2 or 3 studio days in a row, my anxiety jumps, I feel a sense of meanginglessness, I get irritable, and I’m generally not great to be around. It gives me purpose and it gives me a connection to the world and to our collective humanity. I hesitate to put an air of religiosity around painting, but the more I do it and the more I look at the world, the more important painting and art and beauty and thought become. I think we live in a place and time where the arts, and the visual arts especially, are easily dismissed as incomprehensible, condescending, pretentious. And I think our future suffers more for it. If I can imbue meaning or emotion or what have you in my work, then hopefully I can be a part of laying a foundation of meaning for the future.

MHM: Ending on a lighter note… Say you go out for a walk after reading this question. What is your favorite color that you see during your walk?

AC: Right now it is a cold winter evening in the Midwest. The leaves and the summer green are gone, and the dry yellow-brown rustles in the wind. A beautiful aspect of this part of the country, where the Eastern forests dissolve into the Great Plains that stretch from my doorstep to the foothills of the Rocky Mountains, is the sky. With no trees or peaks to obscure it, the sky, the clouds, in their ever changing kaleidoscope of color and shape, stand out from the otherwise muted landscape. In the late afternoon, with the sun shining low on the horizon, the clouds take on a combination of deep orange and vibrant pink. It’s really incredible.

Adam Crowley makes paintings in the landscape and still life genre. His work explores concepts of beauty, fear, sadness, hope, frustration, deep-time, and tradition. Originally beginning his photo based work with the idea of removal of the self and monastic transcription of imagery, he has recently come to realize the necessity of beauty and the importance of dialogue between artist and environment.